Fewer than four decades ago, an emerging China joined its first Olympic Games. Like today, geopolitics loomed large at the Los Angeles event.

Members of the Chinese Olympic team line up before the opening ceremonies of the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, 28 July 1984. (AP Photo)

The Beijing Winter Olympics has reaffirmed China as a titan of the sporting world, as well as being an economic and geopolitical superpower. So it may be easy to forget that fewer than 40 years ago, this all-round juggernaut made its first meaningful appearance in the Olympic arena.

That was at the Summer Games in Los Angeles in 1984, when the world was a hugely different place.

It was during the Cold War, and the key strategic rivals then were the United States and the Soviet Union, which was still seven years away from its collapse. The idea of Moscow being a threat to one of the Soviet republics, Ukraine, was unthinkable.

The two superpowers were engaged in tit-for-tat boycotts of each other’s Olympics. The United States and its allies had refused to participate in the 1980 Summer Games in Moscow. In 1984, the Soviets and most of their East European allies snubbed the Los Angeles Games, aiming to destroy them as a spectacle and ruin them financially.

So when the Chinese, who had until then refused to take part in the Olympics because of a dispute over the status of the breakaway island Taiwan, stepped forward to join the Games, they were welcomed. China’s presence was not just a distraction from the boycott but an attraction in itself.

China’s visitors were mystified and appalled.

China, which had been fully recognised by the Americans only since 1979, had novelty value.

Los Angeles was similarly eye-opening for the Chinese, who came from a country still only cautiously opening itself up to the world.

I recall a pre-Games event at which the Chinese athletes were introduced to movie stars including legend James Stewart. The visitors plainly had no idea they were in the company of some of Hollywood’s finest.

A similar jaw-dropper for the Chinese was the Hollywood-suffused opening ceremony for the Games in the Los Angeles Coliseum stadium. It included 84 white grand pianos dramatically materialising with pianists hammering out George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue.”

The visitors were mystified, and understandably appalled, at racist references about Chinese still current in America and elsewhere. For example, comedienne Joan Rivers, who poked remorseless fun at actress Elizabeth Taylor over weight issues, was famous in the 1980s for her jibe: “Elizabeth Taylor has more chins than a Chinese telephone directory.”

It was only in 1981 that the Illinois town of Pekin, named after Peking, formerly the West’s name for Beijing, reluctantly stopped its high school from calling its sports teams “Chinks.”

China performed creditably at the Los Angeles Olympics.

Chinese athletes were a curiosity. Were they any good? The world was aware of China’s prowess at table tennis, but not much else.

In 1974, when I was based in Beijing for Reuters, I came across the results of a Chinese national athletics tournament. Few of the performances were even close to world class. However, in one event China was unlikely to meet much competition. That was “hand grenade-throwing.”

At Los Angeles, China’s 215 competitors performed creditably, winning 15 gold, eight silver and nine bronze medals.

Aside from China’s participation, the Los Angeles Games were notable for other breakthroughs. They were the first Olympics to include a women’s marathon. It was previously believed the race was too strenuous for women. Incredible as it sounds now, until 1960 no race over 200 metres was contested by women in the Olympics.

A second achievement of the Los Angeles Games was that they pulled off the unheard-of feat of making a profit, possibly the last to do so. This had less to do with China’s attendance and more with the aggressive recruiting of sponsors by the Games’ head organizer, Peter Ueberroth. He won an ovation at the Games’ packed closing ceremony.

Aside from the Games, the year 1984 saw two news stories that resonate today. In January, I attended a splashy product launch by a fast-rising computer company called Apple. A boxy personal computer called Macintosh was introduced to the world by Apple co-founder Steve Jobs.

Also in 1984, the word pandemic was making headlines just as it is now with COVID-19. The disease then was AIDS — acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. While its ravages were less widespread than COVID-19, its reach was global and there was no vaccine for the HIV virus that causes it. There still isn’t.

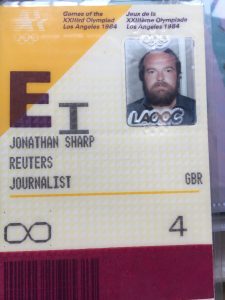

The author’s press card for the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles

Three questions to consider:

- Why had China avoided the Olympics before 1984?

- Why did the Soviet Union boycott the 1984 Games?

- Why haven’t other Olympics been able to make a profit?

Jonathan Sharp joined Reuters after studying Chinese at university. That degree served him well, leading to two spells in Beijing. A 30-year career also took him to North America, the Middle East and South Africa, covering everything from wars to high-tech to the Olympics. His favorite posting was to Hong Kong, where he currently lives.