The 24/7 news cycle turns every news item into a headline without context. The more we consume the news the less we understand. Can we break out of that cycle?

A TV screen fills with the words “Breaking News” while headlines scroll over. (Illustration by News Decoder)

If you’re a news junkie like me, you hang on every latest twist and turn in reports of a political drama. It hardly makes a difference which gripping tale you follow — it’s all breaking news, 24/7. We can’t get enough of it. But those who follow news constantly don’t necessarily get a better understanding of what is happening.

In the background, those urgent facts can pile up into a bigger story that may or may not be noticed. There are people who are paid to hide that bigger story. Just think of the big tobacco company spokesmen who denied the threat to health from smoking. It is our job as journalists to present both the breaking news and the bigger story if that is what’s needed to understand the news.

I’ve been thinking about this recently since seeing it described as “urgent incrementalism.”

We’re getting so focused on urgent news that we can miss what’s building up in the background. If journalism is “the first draft of history,” a tension between the immediate and the eventual is written into the narrative. As Kierkegaard reminded us, life is lived forwards but understood backwards.

We need to balance the “urgent” with the “incremental.” Just because something happened today doesn’t mean it is more important than a bigger story behind it. There is no formula to help locate the balance between the two, but we have to try anyway.

Getting news first should not be foremost.

A few trends in either direction make my journalism antennas stand up and take in the signals.

On the “urgent” side, too many news stories simply broadcast the latest fact without making clear why it might be important. The 24/7 reporting style, with unrelated content running across screens and social media, favors brevity over context. That’s not bad on really important breaking stories — live video can sometimes be the best reporting around. But it quickly fades when overused.

A video medium like television needs to continually show images, even if they’re not very good. But live broadcasts showing cars heading for a scheduled appointment or crowds waiting patiently for a personality to show up add little to our knowledge of an event.

This sense of urgency also creates the scoop-as-marketing. Some reports are billed as breaking news not because they’re important, but just because the station or newspaper got the news first. Or they had a journalist on the spot and others didn’t. That may help their brand image, but it’s not important editorially if it doesn’t push the story forward.

If the “urgent” side can be too rushed, the “incremental” side can deliver stories that appear to be too big or too gradual to handle. Consider the problem of climate change, an enormous threat that many people can’t or won’t take seriously. Stories about it often leave out the important background that many politicians ignore the issue and fossil fuel industry spokespersons try to deny it.

That does not help readers understand the larger story of climate change.

The connection between journalism and democracy

The same goes for the growing threat to democracy. Some leaders reduce the word “democracy” to a synonym for free elections and capitalism. We hear the word used this way all the time. But it usually leaves out the greater context: embedded in the word “democracy” is also respect for the rule of law and trust in the institutions that make it work.

This respect and trust is the intangible glue that holds democratic systems together. It’s an unmeasurable factor that also makes real journalism work. Both are under real pressure around the world now as politicians and propagandists try to hollow out these values to increase their power.

From Donald Trump to Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, these enemies of democracy chip away at our political norms to the point that the democratic system itself is endangered. But it happens gradually enough and often enough that it just gets taken for granted.

Since it is part of their political style, after a while it is not included as context in a news item.

This might sound a bit rich coming from someone who spent 40 years at a news agency — Reuters — that puts out snaps measured in seconds and news stories with often minimal background. It looks like I did then exactly what I criticize now.

Mainstream media divided into camps

When I began my career in 1977, educated readers around the world — our target audience — believed in the democratic system. They saw a world of facts, even if their politicians “stretched the truth” trying to conform to it. If they didn’t live in a democracy, many accepted it as a superior system.

We wrote for that target audience. But a general readership with shared values no longer exists. One could argue about when and why it ended — was it because some politicians began lying more brazenly? Was it because the media became more superficial? Was it a combination of both?

Also, in 2003, I became religion editor at Reuters. That took me out of the front line of urgent news. The joke is that there are only two snaps in worldwide religion reporting — “Pope dead” and “New Pope elected.” The head of the Roman Catholic Church remains the best-known religious leader in the world.

At least by 2016, this U.S. citizen was glad to be in Paris and not having to cover the White House from Washington, D.C. Among other things, Donald Trump said so many things true and false that fact-checkers could hardly follow. Even if he spoke an untruth, we could not say “he lied” because we did not know his mind.

The mainstream media seemed to devolve into opposing camps and trying to find a common ground became more difficult than ever.

Despite it all, I continue to listen to the radio, watch TV and read newspapers of various editorial views. I still write for an idealized general audience, believing a majority of readers believe that facts matter and someone should tell what’s happening with them.

This leaves us back at square one with the tension between “urgent” and “incremental.” Somewhere between the two is a hard-to-find balance that would provide greater understanding. In a world of constant news feeds, this problem in journalism will not likely go away.

If you can solve it, let me know.

QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER:

- What does the author mean by “urgent incrementalism”?

- Why might endless updating of a news story not make someone more informed?

- How might you solve the dilemma the author presents at the end?

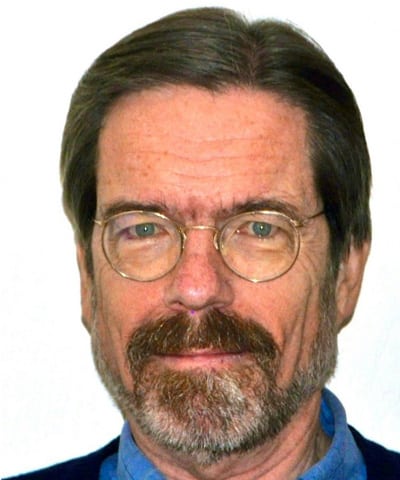

Tom Heneghan was a correspondent, bureau chief, regional news editor and global religion editor during his 40 years at Reuters, with postings in Vienna, Geneva, Islamabad, Bangkok, Hong Kong, Bonn and Paris. He covered the Soviet-Afghan war, two papal elections and Germany’s reunification, which he analyzed in his book “Unchained Eagle: Germany After The Wall”. Based in Paris, he now writes regularly for The Tablet in London and Religion News Service in Washington.

Read more News Decoder articles about journalism:

Good points, and very relevant now with the dramatic news coming out of the Middle East.