Writing should not tie you up in knots. It is no more formal than speaking. Write as you would speak. Think of writing as speaking on paper.

(Courtesy of Lansing Community College Library)

Two authors taught me how to write.

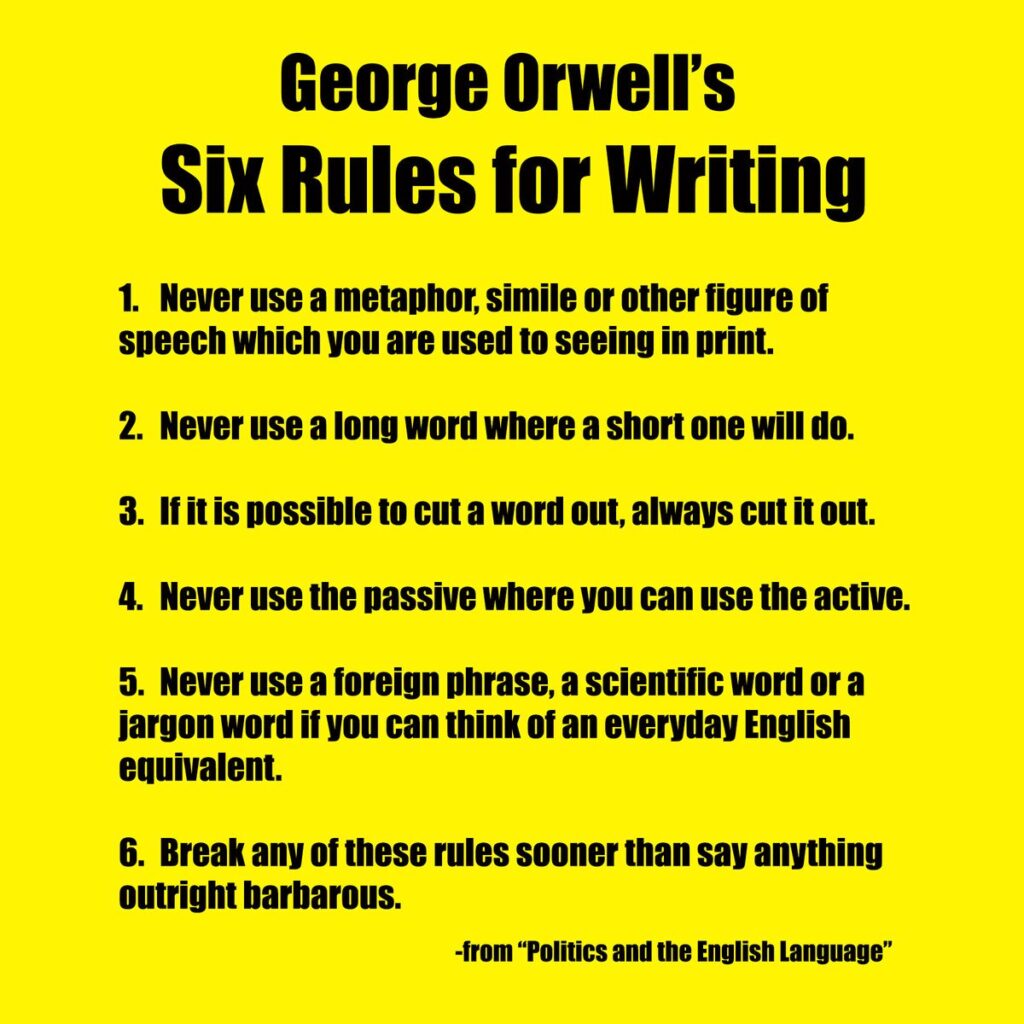

One was British civil servant Sir Ernest Gowers, who wrote “Plain Words” to help bureaucrats speak like human beings. The other was George Orwell, whose essay “Politics and the English Language” showed how clichés and jargon distort and deaden public discourse.

These are dated books, and now we have Grammarly, you may say. But Grammarly is a robot. If you want your voice to come across, you have to develop the confidence to write yourself.

A blank doc. can be scary, but there is no reason why writing should tie you up in knots. The mistake we make is to think that writing is more formal, somehow more special than speaking. It isn’t. Write as you would speak. Think of writing as speaking on paper.

It’s important to get the tone right. A young woman once approached me with an over-familiar email, asking me to look at her grant proposal. The attached document was written in dense, stiff prose.

She had veered from one extreme (“Hi Helen, give me a call!!!”) to the other — “formulating a social policy on how the issuing of Lex Ukrajina has altered the state of cultural cohesion during the refugee crisis.”

Somewhere in the middle between these two styles is the tone I call “polite conversational.” It’s the light, easy tone in which I’m talking to you now.

Some people just love jargon.

There is a geometry to news stories. News is often written in the form an inverted pyramid, with the five Ws — who did what, when, where and why? — at the top.

A feature, on the other hand, will start with an introduction, fill out with your research and findings and come full circle to a satisfying conclusion. You need to know where you are going — not only your beginning but your end. If you know what you want to say, you won’t have any trouble.

In journalism, we say “a picture is worth a thousand words.” But a thousand words can paint a picture, providing you have first seen it clearly in your mind’s eye. See it first, and say it simply. Then the reader will see it, too.

You can easily tell when a person has not visualised what he or she is writing about because they will come up with a “mixed metaphor” (image). Suppose they are trying to describe a project. They might start by talking about “building blocks,” but before you know where you are, they’re on to “roadmaps.” Or Heaven help us, “the pillars of a portfolio.”

What is the poor reader to make of that? Do they mean Greek ruins or briefcases? Construction sites or routes from London to Manchester?

Not every image is going to be original; it’s not easy to dazzle the reader all the time. But if you’ve started with “building blocks,” at least stick with that. In the same paragraph, you might mention “foundations” or “scaffolding”. Then we have a clear picture of a building going up, or the project developing.

Of course, there are writers who don’t want the reader to grasp the meaning, for example the propagandist who deliberately obfuscates. Or the academic who thinks if he drowns you in words, you won’t notice he has nothing to say.

These people love jargon, great long road trains of jargon that will crush you like a kangaroo on the highway.

Be precise and keep it concise.

As a kid, my favourite toy was the Honeywell Buzzword Generator. My father worked in computers, and he brought this invention from Honeywell Inc. home for me to play with. Quite simply, it was two columns of adjectives and one column of nouns. You picked words from each of the columns to create seemingly endless combinations of buzzwords (jargon).

“Leveraging sustainable frameworks” or “robust situational management” or “strategic cross-cutting tools” or “marginalised end-user feedback.” I used to crank them out, faster and faster, and roll on the carpet, laughing.

Now, I am assuming you do in fact want your reader to understand you. Some technical words are unavoidable, but if you find yourself slipping into jargon, stop and think how you might say it in a more straightforward way. “Leveraging sustainable frameworks” = “Using methods that will last.”

Avoid clichés or over-used, ready-made phrases like “it’s not rocket science.” These are a sure sign you are not really thinking. The reader will detect this. If you haven’t switched your brain on, the reader will switch off.

After all, it is the reader we are writing for. So be precise and keep it concise. Vary your vocabulary, using a thesaurus if necessary. You can occasionally allow yourself an unexpected or erudite word. If it is set against a good, plain background, it will shine like a pearl on a black evening dress.

Three questions to consider:

- What do you find difficult about writing?

- Who uses jargon and why?

- Which writers inspire you?

Helen Womack is a specialist on former Communist countries. From 1985 to 2015, she reported from Moscow for Reuters, The Independent, The Times and the Fairfax newspapers of Australia. Since the refugee crisis of 2015, she has written for the United Nations Refugee Agency, UNHCR, about how refugees are settling in Europe. After column writing, Womack went on to write a book about her experiences in Russia: “The Ice Walk — Surviving the Soviet Break-Up and the New Russia.”