Six years after Rohingya fled genocide in Myanmar, a million are still living in a state of legal limbo in Bangladesh. The world seems not to care.

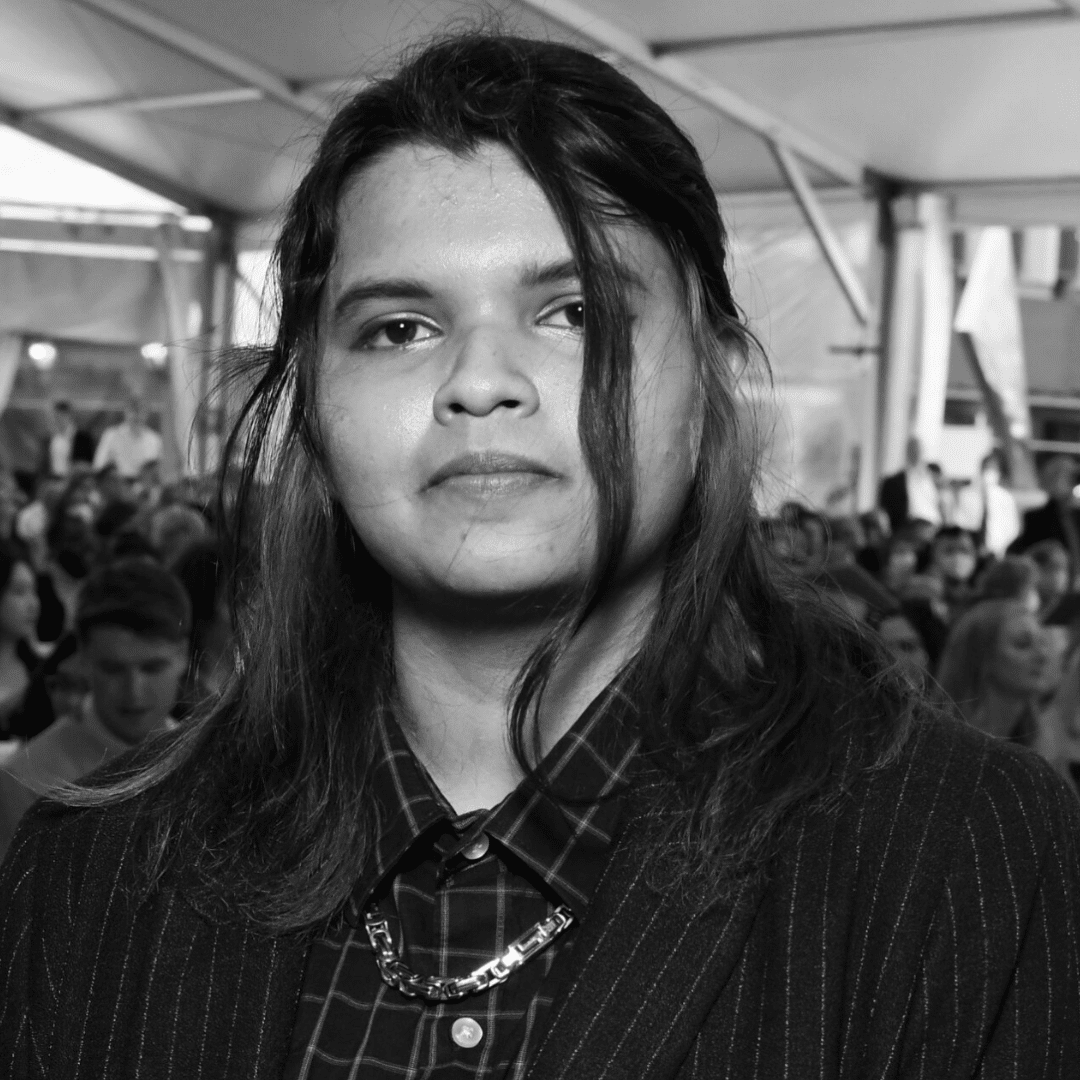

Rohingya camps in Bangladesh. Photo by Norma Hilton.

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

In December 2017, I visited camps in Bangladesh that housed Rohingya refugees. That was four months after the Rohingya fled from genocide in the Rakhine state of Myanmar. I was a student journalist. It was blazing hot and I had to fasten a light blue dress shirt around my mouth like a mask to stop inhaling dust.

The Rohingya people are a Muslim minority in the western state of Rakhine in Myanmar. They have been persecuted by the military of Myanmar and by Buddhist nationalists since the 1970s.

As I walked, I could see makeshift stalls. An old man in a sweater and a lungi, a sarong-like garment that extends to the ankles, sold cabbages, tomatoes, chilies and eggplants. They were propped up against the navy and orange tarpin used to protect a roof from rain. His goatee was white. His apprentice was a girl no older than 17.

The camp wasn’t anything at all like the reports and photographs I had relied on to write and record stories over the previous four months which had described horror after horror.

Here there was no blood staining the ground into a mosaic of crimson, burgundy and scarlet. There was no smoke billowing out from houses set ablaze. Women were not dragged out of their homes and raped in front of their families. There were no babies being burned alive or young boys beheaded.

I took photos of medical tents, supplies from the UN World Food Programme and Australian Aid and the lines of people at food distribution tables waiting for a bare amount of salt, rice, oil and high-energy glucose bars.

Refugees have few rights.

Since 2017, nearly one million Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh, escaping what various United Nations agencies, human rights groups, governments and journalists have called ethnic cleansing and genocide.

Now, six years later, these refugees still live a precarious existence in Bangladesh. Some still live in the camps I visited in Nayapara or Kutapalong — now the world’s largest refugee camp — located in Cox’s Bazaar, a region in the south-east of the country. Others are on a floating island called Bhasan Char in the Bay of Bengal, where their movement, livelihoods and education are restricted by local Bangladeshi authorities.

“Bangladesh does not even officially recognize Rohingyas as refugees, a legal term,” said Maung Zarni, a Burmese human rights activist and non-resident fellow at the Genocide Documentation Center in Cambodia. “[It calls] them ‘forcibly displaced persons from Myanmar’, in compliance with the persecuting state, Myanmar’s insistence.”

Kids in a classroom making a puzzle in 2017. Photo by Norma Hilton.

Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh do not have legal status, which puts them in a precarious position under domestic law and makes them vulnerable to rights violations.

Human Rights Watch reported harassment of Rohingya at checkpoints, closing of their community schools and markets and death threats from criminal gangs on prominent Rohingya leaders like Mohib Ullah, who was shot and killed in September 2021.

The 2023 UN Joint Response Plan for the Rohingya humanitarian crisis received only a quarter of the required $876 million in donor contributions from countries like the United States, Australia and Canada by June this year. This has led to the World Food Programme cutting food rations from $12 to just $8 a month.

Danger from human and natural elements

The mainland camps are overcrowded and susceptible to flash floods and landslides every year. In 2023, flash floods in Bangladesh killed seven people, displaced more than 15,000 Rohingya refugees and destroyed 2,000 shelters, health centres and community centres.

The situation does not fare better in Myanmar either, where about 600,000 Rohingya still live under the military junta that took power of the country in 2021. The junta imposed new restrictions that have worsened water and food shortages and led the way for diseases to spread in camps and villages in Myanmar.

But there are also other threats to the Rohingya in the Rakhine state where a majority of Rohingya in Myanmar live. “The most threat to Rohingya exists from Rakhine nationalists, particularly [the] Arakan Army,” Zarni said.

Reports of the Arakan Army, an armed group in Rakhine state, forcing labour, committing extortions or kidnapping or arresting Rohingya families do not receive attention internationally, Zarni said.

“The Arakan Army leadership is extremely sensitive to any reports,” Zarni said. “It wants to continue to present itself to the UN and other external actors as [an] inclusive and tolerant political actor in Rakhine.”

Home might be even more inhospitable.

The Bangladeshi government began a repatriation program earlier this year after 17 Myanmar junta officials visited the Cox’s Bazaar camps in Bangladesh. Officials in Bangladesh said that an initial group of 1,140 Rohingya refugees will be repatriated to Myanmar and 6,000 will be returned by the end of the year, according to the UN Human Rights Office of the High Commission.

Bangladesh authorities have allegedly misled Rohingya refugees with false promises of resettlement while carrying out verification interviews for the repatriation program to Myanmar. They reportedly threatened arrest, confiscation of documents and other forms of retaliation for those resisting the government’s plans, according to Human Rights Watch.

Repatriation would likely subject Rohingya people to “gross human violations and potentially, future atrocity crimes,” according to UN Human Rights Special Rapporteur Tom Andrews.

Zarni agrees. “The two main barriers are the central military that carried out genocidal waves of attacks and the collaboration of Rakhine nationalists — both are powerful and on the ground in Rakhine,” Zarni said. “The likelihood of Rohingya repatriation successfully and peacefully is not there at all.”

questions to consider:

- Why did so many Rohingya have to flee their homes in Myanmar?

- Why might repatriation of refugees not be a solution to a refugee crisis?

- Who do you think should be responsible for sheltering, feeding and educating refugees who flee genocide?

Norma Hilton is an independent journalist covering everything from K-pop to murder-suicides. She has worked in Canada, the United States, Australia, Singapore and Bangladesh.

Check out more News Decoder stories about refugees and human rights: