Fake news is not going to go away. We need to be selective and responsible. And support news organizations that are credible and trust-worthy.

A woman in the town-library meeting room eyed me suspiciously during my talk on fake news. She challenged me when I referred to a presentation slide with a hoax headline about Hillary Clinton.

“Have you heard about ‘Pizzagate?'” she asked. She was referring to a debunked conspiracy theory about a pedophile ring linked to Democratic officials and centered in a Washington, DC restaurant.

“It’s entirely fake. It’s fantasy. It’s been disproved,” I said.

“I think it’s very real, and I think everyone needs to look it up,” she asserted. With that, she picked up and left.

Thankfully that wasn’t the typical response. Since I started giving presentations on fake news in January in my rural U.S. state of New Hampshire, citizens have filled auditoriums to listen, ask questions and express concern about misinformation flooding their daily news diet.

“Media literacy seems to be incredibly important right now if one is going to be an active citizen,” said Mary Hubbard, assistant director of the Peterborough Town Library, the oldest taxpayer-funded public library in the United States.

It was the state’s library network that first picked up on my offer via social media to lecture on fake news, but I have since spent an hour with callers to New Hampshire Public Radio and been asked to speak to college students.

Even the digitally savvy can be duped.

I made the offer shortly after the 2016 presidential election, when I learned of a Stanford University study finding that digital-savvy students can easily be duped by disinformation about civic issues.

It can’t just be students who are struggling with fake news, I figured. The library audiences, mostly mature adults, bear this out. They raise their hands, along with me, to affirm they have clicked on a headline that seemed outlandish but just-maybe plausible, or mistakenly shared a years-old story as a new development. And they ask how to cope with it all.

The easy part is pointing out how to spot the hoaxes: verify the news outlet, look for phony internet addresses, look it up on a reputable fact-checking site.

Then it gets more complicated: does a story reflect manipulative partisan hype – an unsupported headline or emotive language – or is it open, transparent rhetoric. Does a story originally reported elsewhere get twisted in the transition?

Reporting errors – such as faulty journalism on Iraqi weapons before the U.S. invasion in 2003 – are addressed. And that particular reporting inaccuracy is acknowledged.

Putting state propaganda in context is tricky. It has gained new prominence due to the charges of Russian intervention in the U.S. election and in Europe, but the United States has a long record of its own covert and overt propaganda.

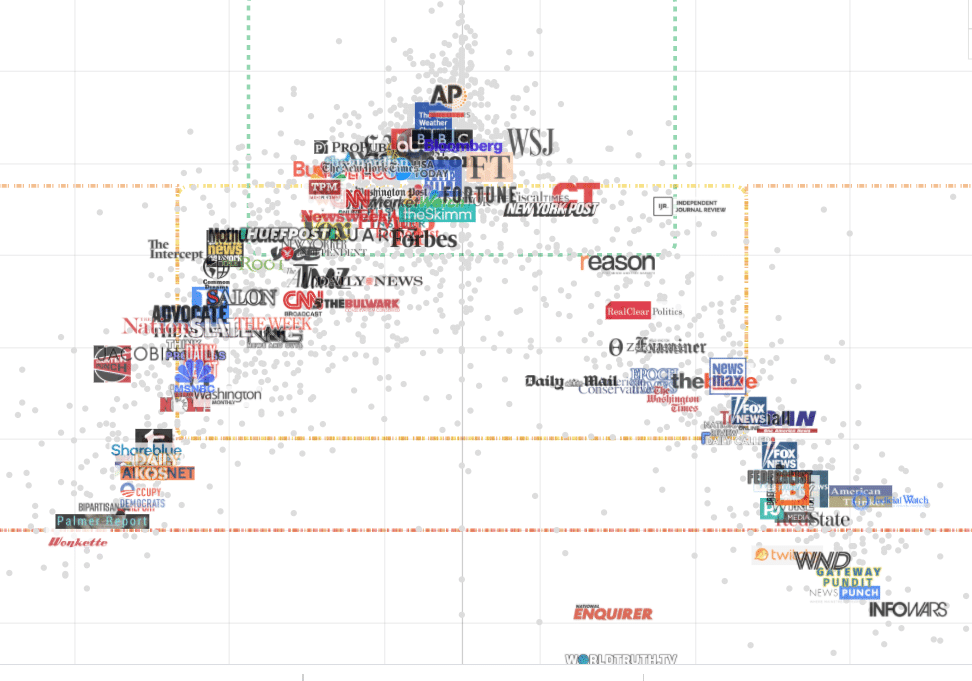

A chart produced by Denver attorney Vanessa Otero plotting U.S. news organizations on a two-way scale of sophistication and political slant draws significant interest and discussion by the audiences.

We have to set limits and be selective.

Then comes the inevitable question: How does a news consumer cope with it all?

For a news professional whose life’s mission has been to understand and convey the affairs of the world, the answer can be ironic.

The sobering conclusion is that even though fake news has always existed, internet economics, political rhetoric and state propaganda are challenging the news consumer like never before.

As news consumers, we have to set limits and be selective. We have to control our social media feeds and be responsible when sharing. We have to balance the desire to be open to alternative perspectives with a need to avoid doubting every news story we encounter.

One questioner asked if I saw any reason for hope. What came first to mind was the post-election surge in paid subscriptions at news outlets considered most credible and professional.

These organizations face a major challenge: to overcome increasingly sophisticated campaigns of obfuscation that aim to undermine media credibility, at the very time their historical business model is under strain.

“We have to pay for it,” I said. “We get what we pay for.”

Randall Mikkelsen has more than two decades reporting and editing political and economic stories for Reuters, including seven years covering the White House and postings in Stockholm and Philadelphia. He helped cover the 9/11 attacks in the United States, two U.S. presidential campaigns, a U.S. presidential impeachment, Guantanamo terrorism trials and the 2008 financial crisis.

Randall Mikkelsen has more than two decades reporting and editing political and economic stories for Reuters, including seven years covering the White House and postings in Stockholm and Philadelphia. He helped cover the 9/11 attacks in the United States, two U.S. presidential campaigns, a U.S. presidential impeachment, Guantanamo terrorism trials and the 2008 financial crisis.