Protesters across the Middle East had been hoping for a second Arab Spring. COVID-19 has driven them off the streets. But for how long?

Imagine yourself as a 20-something in large parts of the Middle East. Fed up with your government — whether because of unemployment, inefficient public services or corruption — you take to the streets in protest.

After weeks and months of organizing and demonstrations, in many cases in the face of danger, you seem to be making progress in forcing governments to take action or commit to much-needed reforms.

Then the coronavirus hits — and you’re back to square one.

This scenario isn’t just hypothetical. It is one that has been a reality for hundreds of thousands of protesters — many, if not most, of them very young — in places ranging from Iraq and Lebanon to Sudan and Algeria.

In 2019 and the very beginning of 2020, many in these countries had expressed hope that a second “Arab Spring” was in the works. Two dictators — in Algeria and Sudan — had already been toppled. In other countries, politicians had resigned and governments were starting to give in to protesters’ demands.

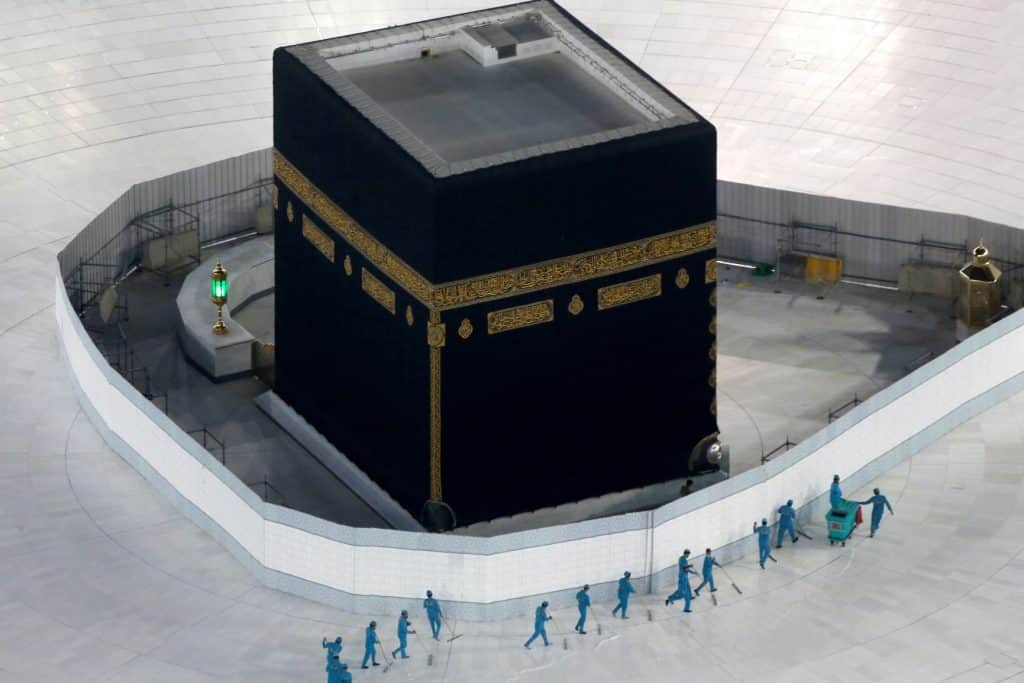

But city squares that not long ago were crowded with protesters have fallen silent. COVID-19 has accomplished in a few weeks what governments had been unable to do for months.

‘More dangerous than the coronavirus’

In Algeria, 56 weeks of protests aimed at bringing down the government and ending corruption came to a sudden halt because of fears of infection. “Social distancing” — keeping apart — does not work in crowds.

“The sense lingers of a job left unfinished,” Bloomberg columnist Bobby Ghosh wrote recently. “For the protesters, the challenge in this time of social distancing is to stay connecting, to remain motivated, and to keep up the pressure on their rulers.”

The protesters aren’t giving up. Around the Middle East, demonstrators are finding innovative new ways to make their voices heard even if they have to stay home. In Israel, nearly 600,000 people tuned into a “virtual protest” against the government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

In the Arab world, government handling of the coronavirus is helping fuel the anger of many young people who will remember how their governments behaved long after social distancing and isolation periods have ended.

“Political parties and corruption are an epidemic that is much more dangerous than the coronavirus,” an Iraqi university student named Mohammad from the city of Diwaniya was recently quoted as saying by the Agence France-Presse news service. “This is the outbreak we want to get rid of because it has destroyed Iraq.”

Fatima, an 18-year old medical student from Baghdad, was quoted as saying that “the real virus is Iraqi politicians.”

“We are immune to almost everything else,” she said.

The coronavirus may fuel more anger.

In the short term — perhaps over the next weeks or months — protests will doubtless lose some of their impact as people head indoors and activism goes online. The need for country-wide responses will likely induce people to defer to their governments, no matter how much they dislike them.

But in the longer term, the coronavirus may fuel more anger.

“These regimes have difficulty addressing relatively basic needs like electricity and schooling,” the Washington-based Middle East Institute wrote recently. “They are bound to further inflame popular discontent with incompetent and corrupt responses to the pandemic.”

This could already be happening. In Egypt, opponents of the government have accused it of price-gouging and attempting to make money off poor workers who need health certificates to work abroad.

“We are the only country that treats any crisis as a quick chance for a quick buck,” a young Egyptian said on Twitter.

So what does this mean for the United States and the West? What can nations outside the region do to prevent a new Arab Spring from descending into war and anarchy in countries like Syria and Libya?

“The United States may not want to assert itself in the region now, but planning for the dire challenges bound to emerge after the pandemic is quite pragmatic,” the Middle East Institute report said. “Regional governments may not have a vision for their own future, but there is no excuse for the United States to join them in pretending that tomorrow will never come.”

At the moment, it’s hard to say what that tomorrow will look like or how we can help other countries when we, too, confront the same crisis at home.

(For more News Decoder stories on the coronavirus, click here.)

THREE QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER:

- What was the Arab Spring?

- What impact is COVID-19 having on protests in the Middle East?

- What do you think the West should do, if anything, to prepare for a possible second Arab Spring?

Bernd Debusmann Jr. is the chief reporter for a business magazine in Dubai. Previously he worked for the Khaleej Times, a UAE newspaper; as a producer on the Reuters Latin American TV desk in Washington; as a Reuters text reporter in New York, and later in his native Mexico, first for Reuters TV and then as a freelance journalist.

Bernd Debusmann Jr. is the chief reporter for a business magazine in Dubai. Previously he worked for the Khaleej Times, a UAE newspaper; as a producer on the Reuters Latin American TV desk in Washington; as a Reuters text reporter in New York, and later in his native Mexico, first for Reuters TV and then as a freelance journalist.