Rwanda is expanding a rural development program that is slashing poverty, but at the expense of free choice. Are the benefits worth it?

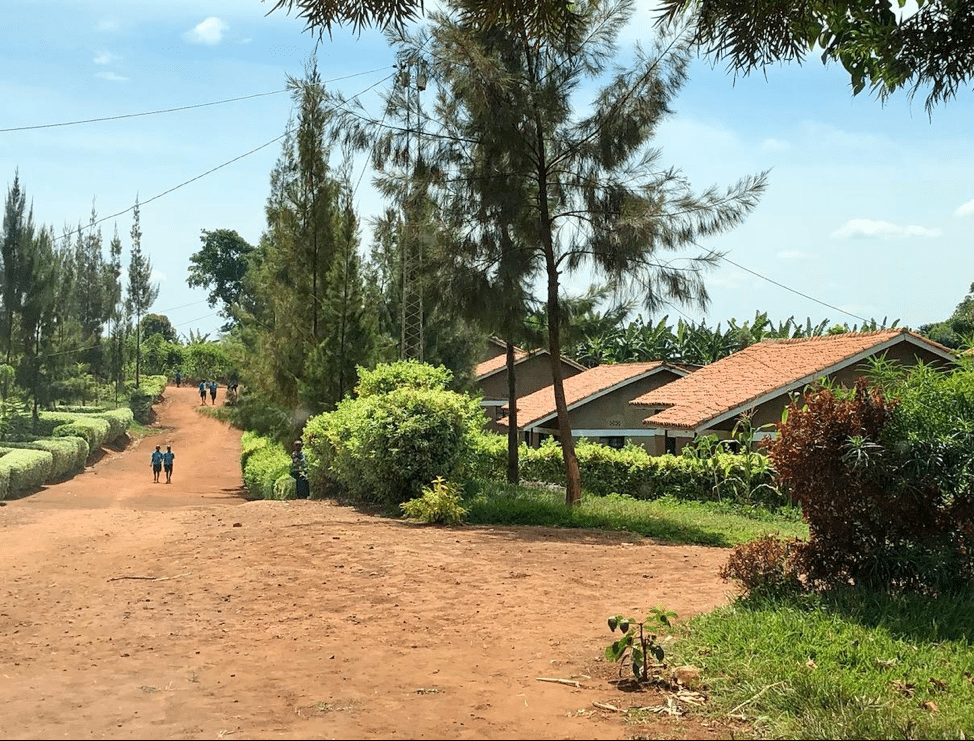

A model village in Rwanda’s Eastern Province that was built in 2016 (Photo by Tara Heidger)

Rwanda is tackling poverty through a controversial rural development program that the government plans to expand aggressively in coming years.

Over the last decade, more than 4,000 Rwandan families have been resettled into model villages. The villages feature three-bedroom brick homes equipped with water, solar panels and sanitation systems, along with social and economic infrastructure.

Rwanda is now expanding the model village program. The government’s goal is to have 70% of the population living in an urban area or village by 2024.

Rwanda is the fifth most densely populated country in the world and the most densely populated in Africa, with 512 people per square kilometer. The hilly terrain and increasingly short supply of land make it difficult to deliver roads, sewers and electrical infrastructure to thousands of scattered farming settlements.

The government sees the movement of people into villages as a way to improve access to public infrastructure and to lift much of the rural population out of poverty.

Model villages are typically home to 200-500 people and can cover five to 10 hectares of land (one hectare is roughly the size of a 400-meter racetrack). Government ministries determine where model villages will be located, taking account of land, development, local government and infrastructure conditions.

The government already owns some of the land devoted to the model villages. In other cases, the government uses its expropriation powers to buy private property.

People are not given a choice about relocation.

This isn’t always a smooth process. A 2017 Human Rights Watch report said a number of Rwandan families were forcibly removed by authorities to make way for a model village. Those who were displaced said their rights to fair compensation and public consultation were ignored.

According to Rwanda’s Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, the 2019/2020 budget has allocated US$31 million to rural development projects, up from $9 million the year before — a 244% increase in spending.

The budget outlines the Rwanda government’s intention to relocate 32,000 of the 455,000 isolated rural households nationwide by 2021. The majority of funding for these projects will come from domestic revenues; international development funds would provide 16%.

Local governments determine who will live in each village. They work off a list of the districts’ most vulnerable people. The vulnerability standards are set yearly and based on a process called ubudehe, where households are ranked by the community to determine each family’s level of poverty based on assets, quality of living structure, disability, gender and the extent to which they were affected by Rwanda’s genocide of 1994.

In some areas, residents vulnerable to landslides — which are commonplace in a mountainous land — get priority.

Residents are granted ownership after five years.

A district committee made up of locally-elected leaders and their staff determine individuals’ eligibility. Once selected, people are not given a choice about relocation. Those who refuse to move are ostracized by the government and cut off from social support until they comply.

The biggest challenge to the model village program is addressing the cultural mindset of the rural population, said John Twahirwa of the Rwandan Housing Authority in Kigali. Moving from the country to a village is difficult, even with the lure of water and electricity and the prospect of owning a nice home.

Under Rwanda’s land tenure laws, new residents are granted ownership of the land and house after five years of occupancy. A contract between the tenant and the district leadership requires that the home be occupied by the designated tenant for five years and not rented out.

Public sentiment about the mandatory moves is mixed.

In interviews with more than 15 recently resettled families, most said they were grateful to have large homes equipped with electricity and running water and access to nearby schools and clinics. One family noted their children no longer risked being burned by candlelight and were able to be more productive after sunset.

Villagization has a long history.

Others were frustrated by the distance they were now required to travel to farm their land — in some cases, further than the five kilometers recommended by the Model Village Program guidelines.

“For the first time in our lives, we have electricity, but no food,” said one elderly couple who became eligible for the program due to their poverty and genocide survivor status. They had previously lived in a rented, thatched-roof home near family and were now far from relatives and sources of support. They now rely on their new neighbors and handouts from local churches for food.

The implementation of model villages — sometimes called villagization — has a long history in sub-Saharan Africa. Human rights groups criticized similar efforts by Ethiopia and Tanzania in the 1980s that resulted in more than 12 million people being forced to move, saying violent and forced relocations resulted in significant rights abuses.

But projects in Ghana, Malawi and Uganda had more positive results, including an increase in school attendance and improved health indicators — potentially due to the projects’ international implementation and oversight.

While it is too early to discern the long-term effects of Rwanda’s program to alleviate poverty, the early indications are that rural poverty has eased.

A 2019 United Nations report on Rwanda’s implementation of its sustainable development goals said the number of Rwandans living below the national poverty line fell from 60% to 38% between 2001 and 2017, while the country achieved all but one of the UN Millennium Development Goals.

Much of the progress has stemmed from efforts outside of the rural development sector. But ensuring homes, infrastructure and social support are available through programs such as the model village program will likely continue to have a lasting impact.

THREE QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER:

- What is “villagization?”

- Why is Rwanda’s rural development program controversial?

- Do you think governments should disregard individuals’ preferences for the sake of achieving an admirable policy goal like poverty alleviation?

Tara Heidger is a freelance journalist based in New York City. She recently graduated from Columbia University with a dual Master of Science in Urban Planning and International Affairs. Her fieldwork in Rwanda was funded by the Earth Institute and the Pat Tillman Foundation.