More than one million people traveled to India in a one-year period for medical treatment. They came for the hospitals in Delhi not the beaches of Goa.

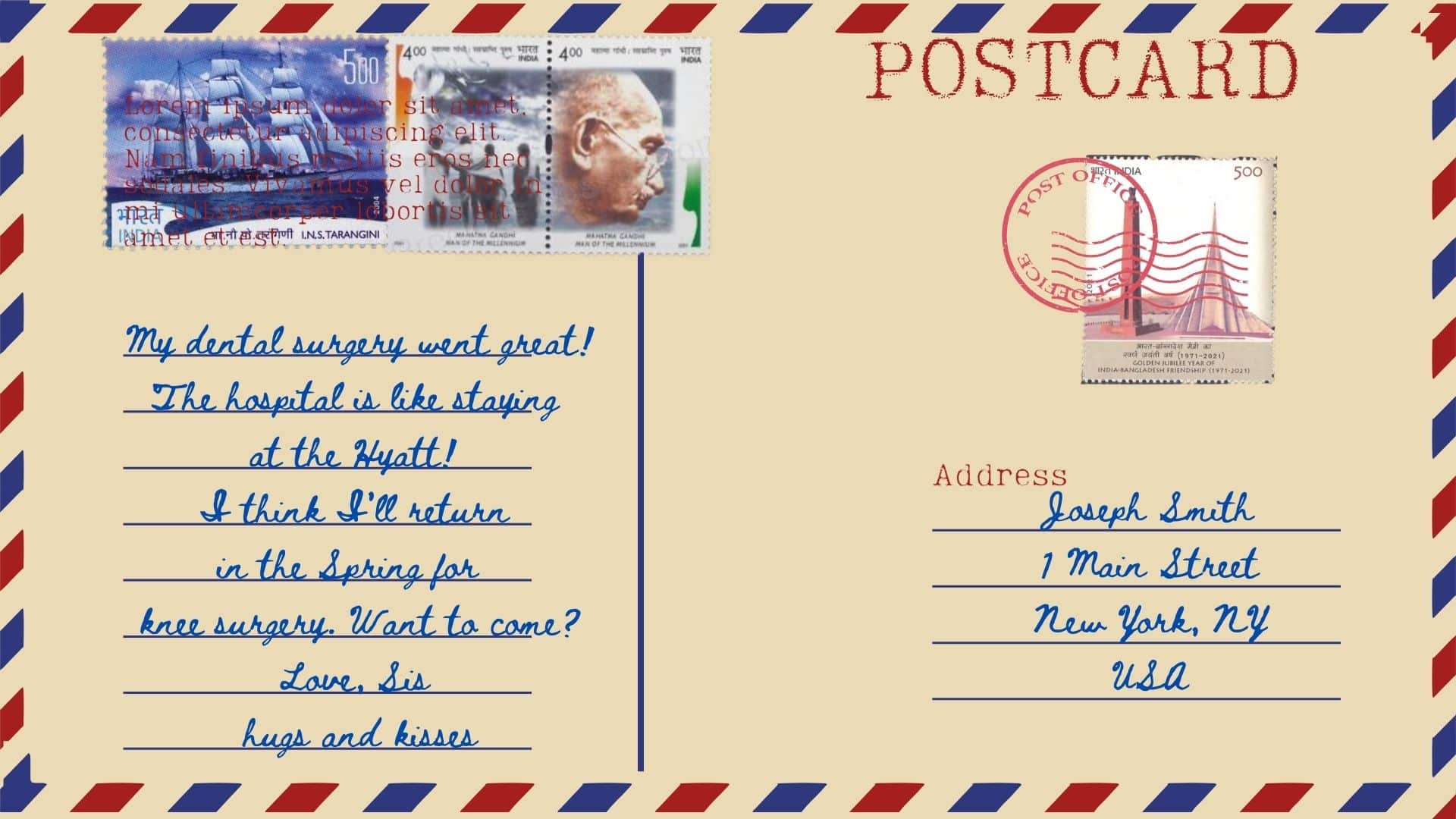

Postcard from a hypothetical medical tourist in India. Illustration by News Decoder.

Even as a majority of Indians struggle to access quality health care services, patients from around the world flock to India’s hospitals for cutting-edge medical expertise at low cost and negligible waiting time.

“If you need medical treatment, it is better to come to India and treat yourself well,” said Shamsudeen Ibrahim, a 34-year-old Nigerian who brought his mother to the Artemis Hospital in Gurugram, a city in the northern state of Haryana, for a follow-up visit after she successfully received a kidney transplant in 2022. “You will have peace of mind and get well soon, inshallah.”

Ibrahim is one of the more than 1.4 million medical tourists who traveled to India between 2022 and 2023, a steep rise from 300,000 visitors in 2021. It was ranked 10 out of 46 destinations in the Medical Tourism Index for 2020-21, published by the International Health Care Research Centre, a nonprofit based in the United States.

Medical tourism refers to the process of traveling to another country to access medical care and treatment. Once an abode of developed countries, now developing nations are aggressively promoting medical tourism in an effort to stimulate their economies.

The Indian government, for example, has launched an online portal to provide credible information to anyone who wants to take treatment in India. It also digitised and simplified its medical visa process and established the Medical Value Travel Council to promote India as a quality health care destination across the globe.

Electing to get elective surgery far from home

Apart from India, Thailand, Malaysia, Mexico and Costa Rica are some other favourite destinations for medical travelers.

Popular for organ transplantation, orthopaedic, spinal, cardiac and cancer surgeries, the Indian medical tourism market is currently valued at $ 6.2 billion and is expected to register a compound annual growth rate of more than 11% between 2023 and 2028.

The market is led by privately-owned large and luxury hospitals. While a large influx of international patients is from Africa, Central Asia and the Middle East, these hospitals also cater to developed countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada and Italy.

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

“The system in developed countries takes a lot of time,” says M. Hayat, manager of the Middle East division at Artemis Hospital. “You need to meet the community doctor first, then go to a specialist and then the hospital consultant. It is not conducive for patients who require urgent attention.”

For hospitals, foreign clients who pay 35–65% more than Indians are a financial boon. “We are bringing in foreign currency,” says Hayat. “It is very good for our country’s economy. It increases the hospital’s share value and brand name, and we get more clients.”

Cost isn’t the only factor.

For international patients, it is not only the low cost and less waiting, but also the quality of treatment that attracts them to India.

“I think there is a certain comfort with Indian health care, even in a foreign setting,” says Swapneil Parikh, an internal medicine specialist based in Mumbai, the financial capital of India. “India produces exceptional doctors and nurses. There are also so many accredited health facilities now. Some hospitals are like luxury hotels. The rooms, the food and the kind of hospitality are just levels above in India.”

Ashwini Setya, gastroenterologist at the Medanta Mediclinic in New Delhi said that 30 years ago, India didn’t have the same technology that was available in the developed world. “Now, there is no technology gap,” Setya said. “You see, the one good thing corporatization has done is bring in investment which has been used to buy great equipment and so on and so forth.”

However, some experts raise serious questions about the adverse impact of medical tourism on the overburdened health systems of developing countries. They worry about increased migration of health care workers from public hospitals to the private health care sector. Limited resources get diverted and local populations get hit with inflated prices of health care services.

A 2019 study, published in the Journal of Travel Research, estimated that what is accepted as the economic contribution of the medical tourism market in developing countries ignores the negative consequences and is overestimated by an average of about 45% as a result.

Catering to medical tourists has costs.

The Indian government, in particular, is criticised for focusing its attention on attracting medical tourists while neglecting the negative effects on the local health system.

Parikh disagreed. “Foreign patients are not going for the healthcare services that a vast majority of Indians are accessing,” Parikh said. “Even the hospitals serving the local population are different. Then there are very strict safeguards in critical areas such as organ donation and infertility treatment. So there is some regulatory attempt to prevent diversion of limited resources to non-citizens.”

Some experts have also raised concerns about medical tourists facing exploitation and receiving substandard treatment.

“It can be a traumatic experience,” said Sumit Roy, critical medicine specialist at the Holi Family Hospital in New Delhi. “International patients in India often face language, cultural and social barriers. Sometimes they don’t understand what is being told to them. Other times, hospitals provide inaccurate explanations to get the footfalls.”

Roy said that some foreign patients end up paying much more than they expected because of unexpected charges or complications.

“In such situations, foreign patients, especially those from Africa, have also faced racism,” he said. “Imagine going to another country, and getting stuck like that with no recourse. Somewhere, we lack empathy for people who come from outside.”

Roy said that the Indian government needs to take proactive steps to regulate the medical tourism market.

“I say this for two reasons,” he said. “One, nobody, irrespective of where they come from, should be exploited. There should be a place where patients coming from across the border can lodge their complaints and be heard. Second, if we don’t regulate the market, our own reputation will go down. That will be counterproductive to the Indian government’s goal of becoming a medical tourism hub.”

Questions to consider:

- Why do people seek medical treatment in India and other developing countries?

- How might the medical tourism market have negative consequences for the healthcare needs of the local population in developing countries?

- Do you think government should regulate the medical tourism market? Why?

Shefali Malhotra is a health policy researcher based in New Delhi and a graduate of the fellowship in global journalism at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto.