Peru has had six presidents in five years. The one constant? A government that reacts with force when people call for change.

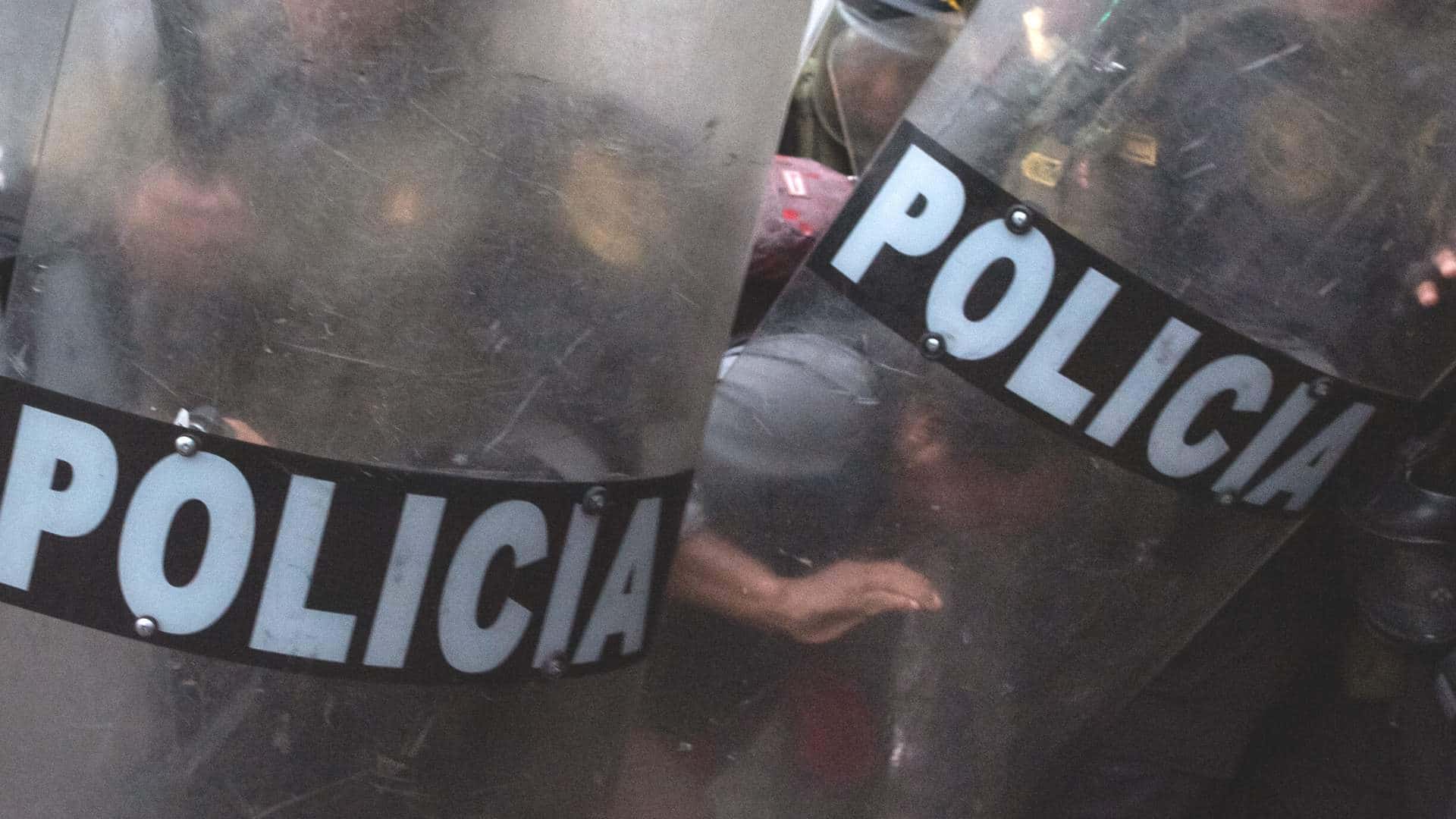

A man beaten by police during the protests against the government of Dina Boluarte in Lima on 4 February 2023. Credit: Alfonso Silva-Santisteban

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

One day in January 2023, Azucena Trujillo was handing out breakfast to protesters staying at the University of San Marcos, the largest in Peru. She saw a police tank-like vehicle cross through the entrance to campus. Behind it, dozens of police followed. Trujillo, an 18-year-old sociology student born in Andahuaylas, ran with some colleagues.

“A helicopter was following us,” she said. “An alarm sounded, and police chased us. They threw tear gas bombs.”

She managed to leave campus through another door. “I saw how they arrested a woman from Ayacucho with her 10-year-old daughter,” Trujillo said. “The police threw them to the ground. These were people we had lived with for a few days.”

After the raid, a policeman recorded himself declaring the defeat of the “terrorists”. Behind him, dozens of people could be seen facing the ground. The police detained 191 people in San Marcos. Among them were elderly and pregnant women. All were released the next day due to lack of evidence.

Jeri Ramon, the president of San Marcos, had called for the raid. But a day later she said: “How was I supposed to know they were going to come in with tanks and go the way they did? I am not in the police force.”

Repressing opposition

The raid in San Marcos was an example of the Peruvian government’s response against those who try to challenge the government of President Dina Boluarte.

Many of these people challenging the government are indigenous people from the Southern Andes. In recent years, several politicians have equated the protests of these people to terruqueo or terrorism.

The last few years have been tumultuous in Peru.

On 7 December 2022, then President Pedro Castillo ordered the closure of Congress and the reorganization of the judiciary and prosecutor’s office. He imposed a state of emergency throughout the country and said he would begin ruling by decree.

Castillo had been a rural school teacher and unionist before running for office in 2021 on a leftist platform that vindicated the poorest.

His government was accused of corruption and inefficiency and opposed by the majority of the Congress. Within hours of his speech, his ministers began to resign. Castillo was ousted by Congress and arrested that same afternoon on his way to the Mexican embassy.

A presidential musical chairs

The vice president, Dina Boluarte, a lawyer from the Andean city of Andahuaylas, became the new president, the sixth since 2018.

Months before, Boluarte had announced that if Castillo fell, she would resign as president, forcing the advancement of elections. When this situation became real, and she was sworn in, she declared that she would stay until 2026.

The outcry in the Southern Andes was almost immediate.

“She quickly sought shelter among the opponents of the government to which she belonged,” said Gonzalo Banda, a political analyst and local pundit. “When she changed sides, the strongholds that voted for Castillo sensed a betrayal.”

The first protests began in Andahuaylas, Ayacucho and Juliaca, areas with a majority of Quechua and Aymara indigenous populations and high poverty rates.

Protesters took to the streets, blocked roads and in some places set fire to public offices. They demanded the resignation of Boluarte, a new constitution to replace the one adopted during the dictatorship of Alberto Fujimoro, an abandonment of neoliberal policies that focus on the private sector over government services and to a lesser extent, the reinstatement of Castillo. These groups identified with Castillo, Banda said. They saw him as a common person.

Protests spread to other cities. Between 7 December 2022 and 10 February 2023, the Ombudsman’s Office registered 1327 protests throughout the country.

Equating protesting with terrorism

From the beginning, the government sought to link the protests, without any evidence, to Shining Path terrorism. During the 1980s and 1990s, Peru experienced an armed conflict in which Shining Path, a leftist fundamentalist group, initiated a struggle in the Southern Andes.

Shining Path conducted massacres, assassinations and multiple attacks. The state’s response included multiple human rights violations.

In 2003, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission estimated that 70,000 people were killed between 1980 and 2000. Most were Quechua-speaking indigenous peasants caught between two fronts.

When Boluarte took power, she declared a state of emergency throughout the country. The army took over the southern cities.

“Instead of dialogue, they sought to repress the demonstrators to achieve the principle of authority,” said Juan José Quispe, a human rights lawyer with the Instituto de Defensa Legal. “It didn’t matter if people were killed or wounded.”

Where protesting means risking your life

The Ombudsman’s Office counted eight deaths during protests that took place during the first week of the new government. Among them was 15-year-old David Atequipa, who was shot while watching the confrontations in Andahuaylas, the town where Boluarte was born.

On 15 December 2022, a group of protesters tried to enter Ayacucho’s airport. The army responded. Ten people were killed. Footage of the clashes shows soldiers firing at civilians from a distance.

“Taking out the army in Ayacucho was like reviving memories of the 1980s,” Quispe said. Ayacucho was the city where Shining Path began its activities. For years it was under army control.

The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights documented the deaths of 50 civilians and the injury of 821, allegedly by security forces between December 2022 and March 2023.

“Security forces used unnecessary and disproportionate force, including lethal force, outside the circumstances permitted by international human rights law,” stated the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in its report.

Clashes at the airport

On 9 January 2023, the scene in Ayacucho repeated in Juliaca, a busy city close to Bolivia and with a majority Aymara population. Near the airport, a group of protesters clashed with the police. The army began firing.

Marco Samillán, a 30-year-old medical intern, was treating a wounded man when he was shot in the chest. Seventeen other civilians were killed that afternoon.

Boluarte declared that the ammunition that killed the protesters was likely to have come from abroad, implying that protesters had killed each other.

Then the government insisted that organized crime was behind the protests, and again, no evidence was shown.

Following the killings in the south, thousands of demonstrators came to Lima. During January and February, marches were frequent in the capital. The government deployed thousands of police in the streets, who at times marched in parade formations.

Some students at the University of San Marcos decided to house protesters on campus.

“They were looking for a space to sleep without the police harassing them,” says Frank Cruz, a sociology student. “About 500 people arrived. Families from Puno, Cusco, Apurimac. We decided to use the common areas.”

A raid on a university

The students gathered donations and prepared food. Five days later, the police raided the campus. “It was a symbolic blow to make you understand that you can’t do anything, that they have the power,” says Cesar Miranda, an archeology student.

In May, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights recommended that the Peruvian government bring those responsible for the killings to account and provide reparations and assistance for victims of human rights violations.

During a follow-up hearing in November, relatives of the victims testified, denouncing multiple delays in the investigations. Nobody has yet been found responsible for the deaths and injuries.

After Gustavo Adrianzen, Peru’s ambassador to the Organization of American States, spoke on behalf of the Peruvian state, a group of people burst into the room, accusing him of lying. Adrianzen took the microphone and shouted, “They are the violent ones! They are the ones who caused the deaths!”

It was an unusual reaction for a diplomat, but one that seems to sum up the government’s stance over the last year.

Three questions to consider:

- Who are the people protesting the policies of the Boluarte government in Peru?

- Why would a government fear people who peacefully protest?

- In your country, what do people protest for or against?

Alfonso Silva-Santisteban is a public health physician, researcher and photojournalist based in Lima, and a former fellow in global journalism at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto.