Photojournalists tell stories through images. To do that they have to get into the thick of it.

A man is arrested during the protests against the government of President Dina Boluarte in Lima, Peru on 4 February 2023. Credit: Alfonso Silva-Santisteban.

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

I heard the rally even before I saw it.

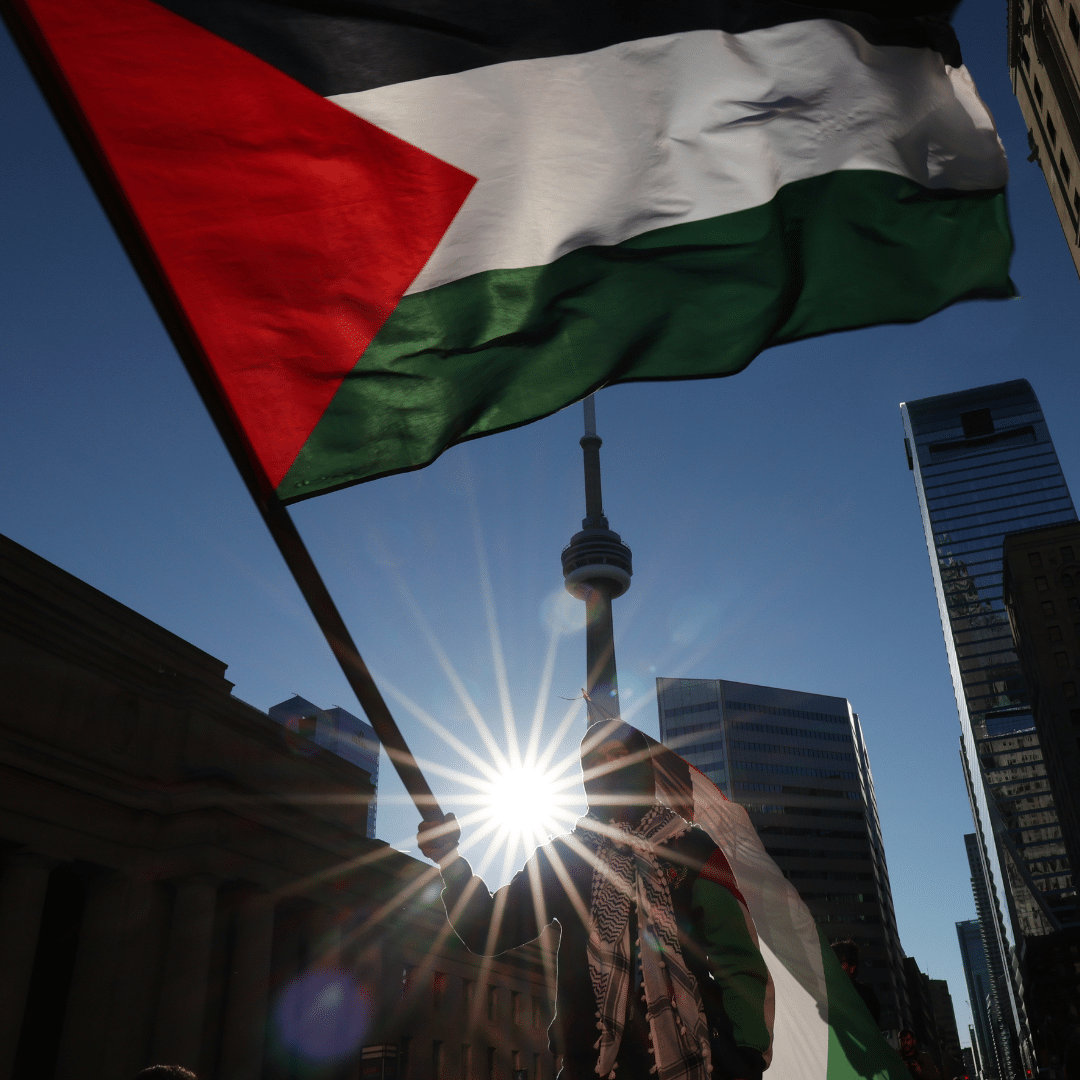

Car horns blared, insisting the way to my destination was after the next right. It was 12 November and I was headed for a rally at Nathan Phillips Square in Toronto, Canada of people demanding an immediate ceasefire in Palestine and Israel.

It was the first rally I would cover as a journalist. It was not the first one I’d been to or the first I’d witnessed from a distance. Having grown up in Bangladesh, I’d had plenty of experience, missing most of the in-person classes in the last two years of high school because of violent political clashes in the capital city of Dhaka.

At the rally in Toronto, I took photos with my iPhone of a few of the most critical signs, a young man holding the Palestinian flag, banners of support from the Indigenous communities in Canada and two individuals on top of a bus stop setting off green and red flares.

As a journalist, I needed the photos I took to tell an important story.

The tone of an event

Also at the rally taking photos was Richard Lautens, a photojournalist with The Toronto Star newspaper who has 36 years of experience. I decided to ask him and other photojournalists for advice covering live events like a rally.

“Try to capture the tone of the event,” said Lautens.

The most important thing when covering a protest or march is to make sure we see faces, Lautens said. “If people are angry generally or if they are demanding some change, we need to see every face as they are yelling or looking sorrowful,” he said.

Two protestors holding up flares at the Ceasefire Now rally at Nathan Phillips Square in Toronto, Canada on 12 November 2023. Credit: Norma Hilton.

The freedom to make one’s voice heard is a democratic right many people in Canada exercise. Most protests and rallies are peaceful demonstrations demanding change at home or abroad.

Research your subject before the event.

On 12 November this year, demonstrations took place across the country by an organization called Ceasefire Now which called for an immediate ceasefire in Israel-Palestine.

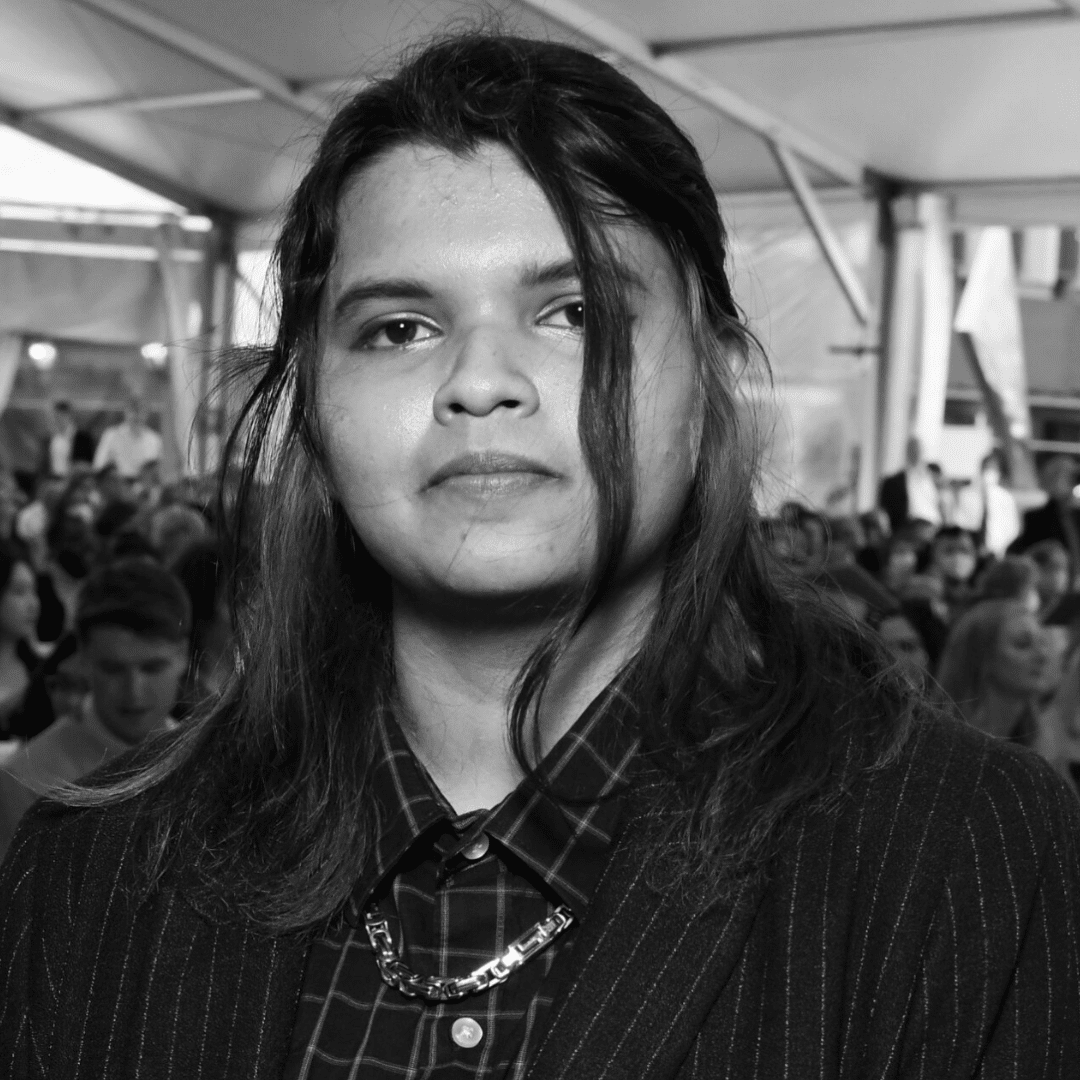

When covering an event your job as a photojournalist begins before the event, said Fabeha Monir, a Bangladesh-based photographer and journalist who has worked for organizations like the World Health Organization and The New York Times. “It’s essential to first gather information about the protests,” she said. This is especially important for women journalists just starting out in their careers, she added.

“I was always careful when and where to position myself,” Monir said. “We need to always change our position and try to get different angles from different points of view.”

Moving around during protests in Bangladesh can be incredibly difficult. Human rights organizations like Amnesty International reported demonstrations in the country frequently turn violent with police exerting excessive force to disperse protestors.

Safety is most important.

This includes using tear gas, rubber bullets and sound grenades. On 28 October 2023, dozens of journalists were also injured, becoming collateral in clashes between supporters of Bangladesh’s two largest political parties ahead of the 2024 elections.

Monir said that the many times when she was on assignment and the protests became violent, the first thing she cared about was her safety. “I was stopped for taking photographs and requested not to show faces,” Monir said.

News Decoder correspondent Alfonso Silva-Santisteban is a public health researcher who’s been photographing protests in Peru for about three years. He tries to share what he sees at the scene.

“Who is there? Why? How is the mood? Are people enraged, or are they just manifesting their discontent? How many people are there?” he said.

Silva-Santisteban also focuses on authority figures like the police who have historically used excessive force to thwart efforts to organize and protest against deep ethnic divisions in Peru.

A woman being treated for injuries sustained during clashes between garment workers, who demanded fairer pay, and police earlier this month outside Dhaka, Bangladesh. Credit: Fabeha Monir.

Know the limitations of your equipment.

In the first three months of this year, the country saw protests demanding new presidential and congressional elections. It was some of the most intense protests in at least a century, where security officers used live ammunition on protestors at close range. At least 60 people have been killed.

“You can quickly perceive if police are going to accompany a rally or if they are going to clash with the people,” he said. “The sort of images that can give a sense of the context and kind of put who is looking at the photos in the scene.”

Part of my apprehension with covering the rally at Nathan Phillips Square was my lack of proper photography equipment. I had nothing but my iPhone camera with me.

Lautens said there is no problem with a camera phone, as long as you are aware of the limitations of the equipment.

“Be prepared to stand closer than your comfort level to fill the frame,” he said. “You should come back with hundreds of photos from an event, as many [taken] with a smartphone will not be usable due to slower shutter speeds and ability to time the taking of your photos appropriately.”

Be where the action is.

It is important to get comfortable with whatever equipment you use until it becomes second nature, Lautens said.

Silva-Santisteban agreed: “Current phones are very versatile for shooting photos and videos, and they are easier to manage,” he said. “They also allow you to share the material almost in real time.”

The main difference when using professional equipment, he said, is that it gives you greater control. But that should not deter anyone.

“As a very experienced photographer told me once, the most important component is to be where the important things are happening,” Silva-Santisteban said.

When I first moved into the crowd, I found myself nearly getting pushed to the ground because of the sheer number of people around. Instinctively, I moved to an elevated area where a tree was yet to be planted and I was free to take as many photographs as I wanted. A more experienced photojournalist might not have done that.

“Move your feet, walk through and around the crowd at regular intervals and get in front of people,” said Lautens. “We want faces.”

Photographers often take too many photos of anyone who is speaking, and that’s another major mistake, Lautens said. Speakers usually make for very poor images. Anyone who is very important is worth a photo or two at most.

You want to be in the middle of the action and emotion. Silva-Santisteban said that’s why it’s so important to be prepared– to know the context of where you are, have proper protection equipment, avoid going by yourself and stay in contact with someone who can monitor the situation. The most important thing is to stay safe.

“No photo is worth risking your life,” he said.

Questions to consider:

- As a journalist, what are some key things you should look for while shooting protests or rallies?

- Is it possible to shoot high quality images on a budget? What’s the biggest difference between using a phone versus using a professional camera?

- What are the issues a photographer should be aware of while photographing protests or rallies?

Norma Hilton is an independent journalist covering everything from K-pop to murder-suicides. She has worked in Canada, the United States, Australia, Singapore and Bangladesh.

Read more News Decoder stories about photojournalism: