Henry Kissinger died on the 29th of November. Our correspondent remembers the one time he had the opportunity to question him directly about his lauded career.

U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger being congratulated 16 October 1973 by U.S. President Richard Nixon in the Oval Office of the White House, following the announcement that Kissinger was a winner of the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize. Kissinger and North Vietnamese diplomat Lo Duc Tho won the prize together for their efforts in ending the Vietnam War. (AP Photo)

This article was produced exclusively for News Decoder’s global news service. It is through articles like this that News Decoder strives to provide context to complex global events and issues and teach global awareness through the lens of journalism. Learn how you can incorporate our resources and services into your classroom or educational program.

I had one question for Henry Kissinger. This was back in 1999 in Geneva.

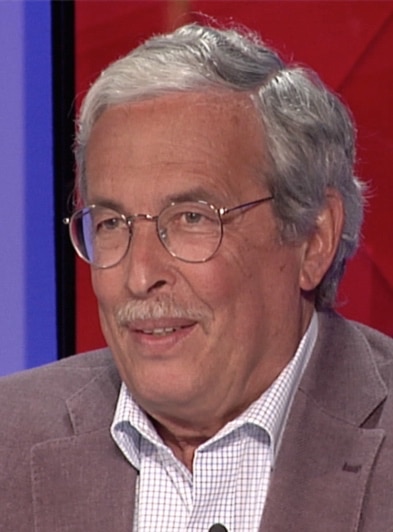

The famed statesman died 29 November in the U.S. state of Connecticut.

His death has elicited varying reactions. Some considered him Super Henry for what became known as “shuttle diplomacy” as he pursued peace between Israel and its Middle East adversaries in the wake of the Yom Kippur War and for establishing a relationship between the United States and China. Others considered him evil for Machiavellian policies in Chile, East Timor, Vietnam and elsewhere. As U.S. National Security Advisor in 1969 he authorized the bombing of Cambodia.

For me, it brought back memories of his presence in Geneva in 1999 when I had an opportunity to question him directly about his career.

Why did Kissinger come to Geneva? He was a friend of Professor Curt Gasteyger of the Geneva Graduate Institute. I knew that because I had written a critical assessment of Kissinger’s Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy as a student in Gasteyger’s seminar. I was deputy to the director of the Graduate Institute of International Studies at the time.

A question worth 100 Swiss francs

In my paper, I had given an overview of the negative reviews of the 1957 bestseller that launched Kissinger’s career. Gasteyger had rejected my paper with an explanation of the importance of Kissinger and their relationship.

Gasteyger had invited Kissinger to come to Geneva to celebrate an anniversary of his program in international security. I bet with Gasteyger Henry wouldn’t come. Geneva, in my opinion, was too small for him. The bet was 100 Swiss francs. If Kissinger came, I would have the first question. If he didn’t, Gasteyger would pay me the 100 Swiss francs.

Kissinger came. I spent weeks preparing my question. What to say to a man I felt responsible for prolonging the Vietnam War among other unethical policies? How to be polite in front of a packed distinguished Geneva audience?

How to be diplomatic in front of that audience while asking what I really wanted to know?

“Dr. Kissinger,” I began, trying to sound as respectful as I could, “in your long and distinguished career, is there anything you regret, is there anything that you would have done differently?”

Answering for a legacy of war and peace

I was sure he heard my New York accent. He was raised in Inwood Park in the Bronx. I was raised near Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx, not far away.

He saw my age. For a moment I was back in the 60s, my hair longer, my voice more strident, screaming that Kissinger and Nixon were war criminals. I spent the Vietnam War in New York City, teaching in the South Bronx and Harlem.

Did he hear me then? Did he hear me now?

He gave me a look of condescension. He made it known that the question was misplaced, irrelevant. He had no qualms about any of his actions.

“Young man,” he pontificated, “if you mean Vietnam, it was the highlight of my career.”

People applauded. I was stunned. Fifty seven thousand Americans dead. Millions of Vietnamese. Many who died could have lived had he stopped the war earlier. We learned that well before 1999.

At the end of the evening people left the auditorium in awe of him and his verbal dexterity. Years later, friends have told me they remember my question.

Super Henry or Evil Henry? That evening all his diplomatic finesse was on display. And that day, the Geneva audience, except for very few, were duly impressed.

questions to consider:

- Who was Henry Kissinger?

- Why was the author surprised by Kissinger’s answer to his question?

- Do you think that deaths in war can be justified?

Daniel Warner earned a PhD in Political Science from the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, where he was Deputy to the Director for many years as well as founder and director of several programs focusing on international organizations. He has lectured and taught internationally and is a frequent contributor to international media. He has served as an advisor to the UNHCR, ILO and NATO, and has been a consultant to the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Defense of Switzerland as well as in the private sector.