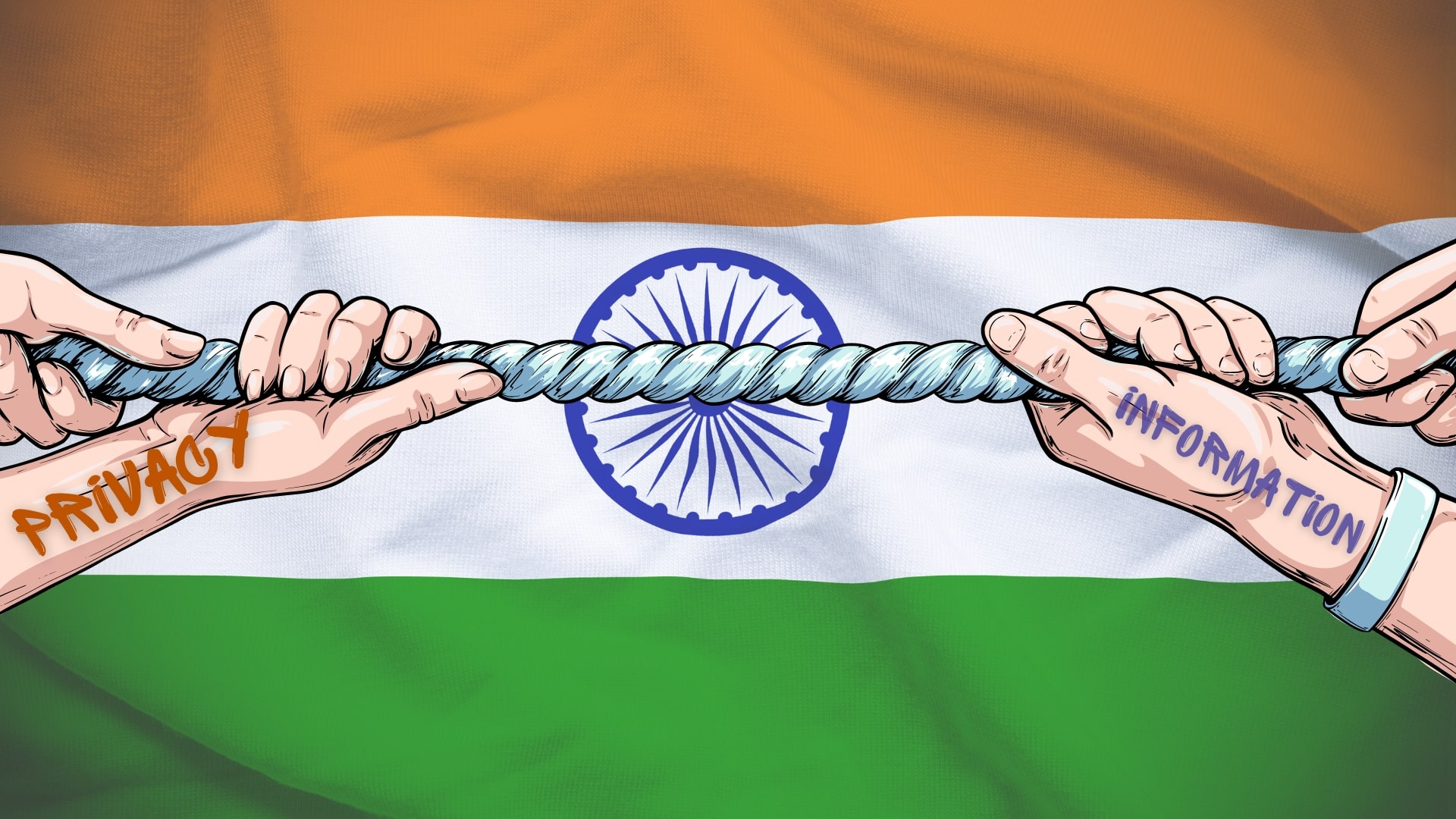

The Indian government has proposed strengthening privacy protection, but at the cost of transparency. Is this about protection or repression?

Photo illustration by News Decoder.

India’s proposed digital privacy law is creating fault lines between the right to privacy and the right to information.

Known as the Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, the law would amend another law, the Right to Information Act 2005, which empowers Indians to access information under government control. The amendment would exempt the government from disclosing personal information to the public.

“The [proposed] amendment is very regressive,” says Anjali Bhardwaj, co-convenor of the National Campaign for People’s Right to Information, a coalition of organizations and individuals in India that supports ordinary citizens exercising their right to information. “In the name of privacy, it will take away the citizens’ right to transparency, right to hold the government accountable and stop corruption that affects them.”

The right of access to information held by public authorities is recognised as a fundamental human right under international law.

Regarded as an essential tool for the citizens of a functional and vibrant democracy, access-to-information laws had been adopted in 135 countries as of 2022. India recognised the right to information as a fundamental right under its constitution back in the 1970s and enacted the Right to Information Act 2005. This law as been used by Indian citizens to expose corruption and ensure delivery of basic rights and entitlements guaranteed under various laws and government schemes.

Bhardwaj offers this example: People living in slums in Delhi, India’s capital, were not getting their rations, the subsidized food grains — such as wheat, rice and sugar— that they are entitled to under a public distribution system. Shopkeepers would tell them that their rations had not reached the shops.

The slum dwellers filed right-to-information requests to find out what happened to their rations. The information they got revealed there were a host of ghost names on the list of beneficiaries — people who either did not live in those slums anymore or had died a long time ago. It also revealed that the rations were reaching the shops every month but were not being given to the people.

“Using this information, the people were able to hold public hearings and file complaints,” Bhardwaj says. “The government was now forced to take action and fix the problem.”

Privacy protections are important

The drafters of the right-to-information law understood that sharing information should not unnecessarily invade any person’s privacy.

So, the government is not required to disclose personal information if it is not related to a public activity or interest, or it causes unwarranted invasion of someone’s privacy.

Even this information can be disclosed, if the information officers of the central and state governments are satisfied that there is larger public interest involved.

In any case, information that cannot be denied to the Indian parliament and state legislatures can also not be denied to any person.

Do government officials have privacy rights?

Access-to-information laws in other countries also contain exemptions protecting personal privacy. Conflicts frequently arise between the two rights because governments often cite privacy to deny information to citizens.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, personal privacy and law enforcement records concerning individuals were the two most-used exemptions to the federal Freedom of Information Act in the United States in 2022. In comparison, in the United Kingdom, 41% of all refusals to share information in 2021 were to protect personal privacy.

In India, 35% of all refusals relate to personal information, says Bhardwaj.

The proposed digital privacy law seeks to change this provision to exempt the government from disclosing personal information under any circumstance, whether there is public interest involved or not.

In Bhardwaj’s example, it would mean that the government would neither be required to disclose the list of beneficiaries entitled to subsidised food grains nor the records of ration shops.

“This is bizarre,” says Alok Prasanna Kumar, co-founder of the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, a think tank that conducts law and policy research in India. “There is no question of a right to privacy in the context of public functions.”

Is privacy a fundamental right?

This is not the only criticism that has been leveled at the Indian government’s proposed digital privacy law. At a public meeting held in New Delhi on 17 March, some experts called the proposed law a government protection bill rather than a data protection bill.

“The Indian government sees data protection as protection from some companies only,” says Anushka Jain, policy researcher with the Internet Freedom Foundation, a New Delhi-based nonprofit that advocates for the digital rights and liberties of Indians. “But government itself is the biggest data processor in the country. Instead of protecting citizens from surveillance, this law will allow the government to exempt itself and its agencies from complying with its provisions.”

According to Kumar, the law does not provide a mechanism through which it can be enforced. “The government is basically saying there is no right to privacy against it,” he says. “It can do whatever it wants, however it wants, whenever it wants. People will have no remedy. If they want, they can sue private companies. But the law does not say how.”Some experts feel that privacy activists in India have gone too far in their demands. One line of argument is that the 2017 decision by India’s highest court to recognize the right to privacy as a fundamental right under the Indian constitution was not well thought out.

“Respect for bodily integrity and personal space have been recognized by Indian courts before 2017,” says Prashant Reddy, an Indian lawyer and author. “The 2017 judgment elevated privacy of personal information to the level of a fundamental right. This has huge implications for free speech, journalism and transparency. It’s a big conceptual mess, if you ask me.”

According to Reddy, the public interest exception to disclosing personal information under the right-to-information law can no longer be justified, as it is too broad an exception to encroach upon a fundamental right. “It’s a different thing that the government and bureaucrats have jumped on this opportunity,” he said. “But, theoretically speaking, what they are doing does have a justification.”

How can competing rights be balanced?

Others believe that privacy activists need to consider the realities of India. “Privacy advocates only talk about their personal relationship to the state,” says Kumar. “Most of them are well off. They don’t need the state. They fund the state. But that is not 90% of this country. For them, state is the only thing holding them back from complete destitution, whether it is giving pension or education or health.”

The Internet Freedom Foundation’s Jain says transparency does not mean that people give up their privacy. “Our demand is to regulate public authorities and companies to make sure that the data they are collecting is necessary and proportionate to the purpose for which they need it,” Jain said.

Bhardwaj argues that the right to information and the right to privacy should be balanced.

“If information advocates want the list of all patients with their ailments, they are going too far,” she says. “Similarly, if privacy activists say electoral rolls should be out of the public domain, they are going too far. But I don’t think we can make generalized statements.”

The issue overall, she said, is the public interest in a democracy. “Nobody wants a situation where the government is doing surveillance but we also don’t want a situation where the government ends up making itself unaccountable,” Bhardwaj said. “Right now, both privacy and transparency activists are very clear that this law is totally useless.”

Finding a balance between the two rights is “not mathematical, of course,” Kumar said.

“It is something that we will have to decide as a society — this is the right way to do something and that is the wrong way,” Kumar said. “In that sense, the mechanism for finding the balance is already there in the right-to-information law. But with the digital privacy law, there will be no question of finding a balance.”

(Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, which is based in Delhi, Bengaluru and Mumbai.)

Three questions to consider:

- How does the right to information empower citizens to hold the government accountable?

- Why is there a tension between the right to information and the right to privacy?

- How can the right to information and the right to privacy be balanced?

Shefali Malhotra is a health policy researcher based in New Delhi and a graduate of the fellowship in global journalism at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto.