I covered SARS and watched the spread of HIV. For me, COVID-19 has been altogether different — in part because I had to fight it off.

Viruses, I’ve seen a few.

Singapore was the first place I found myself covering a new virus epidemic when SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) hit in 2003. Two decades earlier, I was working as a young journalist in Sydney when Australia’s first case of HIV was diagnosed.

But the 2020 coronavirus outbreak was totally different.

For the first time, instead of managing the coverage or watching from the sidelines, I experienced it firsthand. In March this year, soon after moving back to Sydney from the UK, I developed flu-like symptoms including a debilitating cough, and was confirmed positive for COVID-19.

I was the hospital’s first COVID-19 admission.

What followed was an ambulance ride to the nearby hospital, necessary because transport options are limited with a highly communicable disease. Then, I was isolated in an examination room while a mobile radiology unit was wheeled up to the glass window to X-ray my lungs.

It wasn’t a pretty picture.

With a lung X-ray full of white patches, I had to stay in the hospital’s infectious diseases section to improve my blood oxygenation and be dosed up with antibiotics and anti-coagulants.

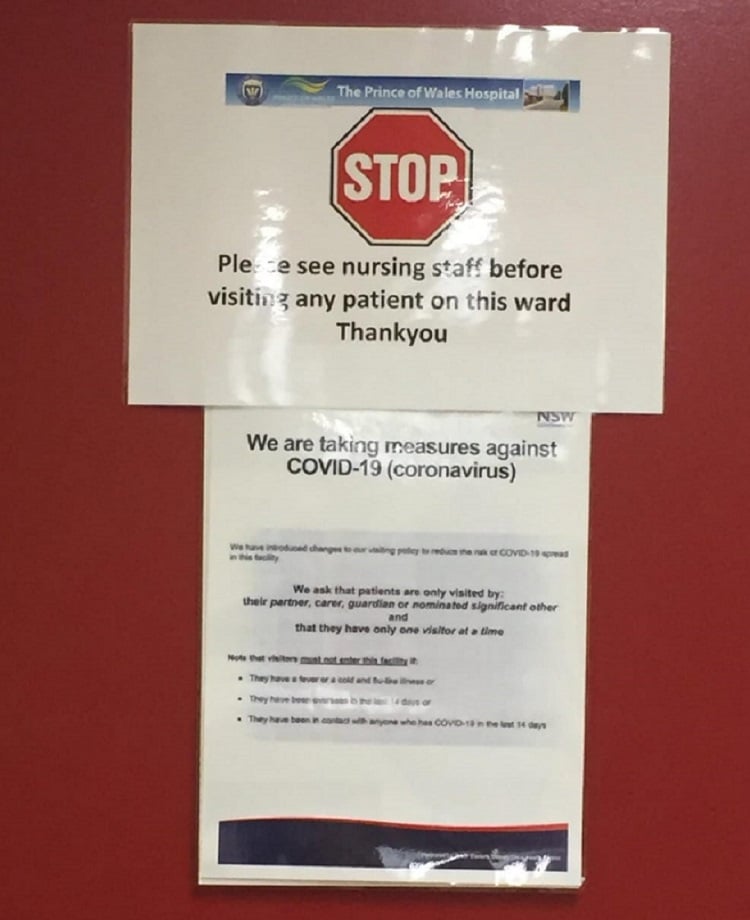

Thankfully I didn’t need a ventilator or intensive care, but the hardest part about dealing with coronavirus was the isolation. Hospital staff kept visits to a minimum to preserve the personal protective equipment that had to be worn in my room. And, of course, no visitors were allowed.

I was, in fact, this hospital’s first COVID-19 admission, so I got to play a useful role in helping them develop and test procedures and discharge protocols for handling what was then expected to be a tidal wave of patients with the fast-spreading infection.

Our reporters were worried about covering SARS up close.

Up until this very personal COVID-19 experience, my main involvement with new and deadly viruses had been while I was the local bureau chief for Reuters during an outbreak of SARS in Singapore in 2003.

A young woman had been infected with SARS while holidaying in China and had returned to Singapore, triggering a chain of transmission across the city state.

During the SARS outbreak, there was a lot of worry about the spread of the virus and its deadly impact. So when Singapore’s Ministry of Health announced it would hold regular press briefings at the centre where many victims were isolated, our local reporters, who were more familiar with covering financial and business news, were rightly worried about going along.

In the end, it was a case of calling for volunteers to cover the almost daily briefings. If no one wanted to go, I went myself.

SARS was a smaller version of COVID-19.

By the time SARS was brought under control in Singapore, there had been 238 confirmed cases, 33 of whom died — a much smaller version of the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Singapore’s confident management of that outbreak showed me that the public health response is crucial. I think this played a valuable role in my own attitude in coping with being hospitalised with COVID-19 this year.

The earlier HIV/AIDS epidemic in Australia, which began with the first recorded case in Sydney in October 1982, had a lot of similarities to today’s COVID-19 outbreak.

Although I did not report on the story, I remember the fear and uncertainty at the time. People weren’t sure what would happen with the virus, how you could catch it or how large the epidemic might grow. As with the coronavirus now, there was no sign of a cure or any effective treatment.

In the end, Australia got on top of the HIV epidemic as the government swiftly implemented a series of disease prevention and public health services, such as needle and syringe programs. It used a controversial TV ad campaign in the late 1980’s to deliver a strong message about prevention.

As for COVID-19, at last count Australia has recorded just over 100 deaths from COVID-19. Although many more people have been infected with COVID-19 worldwide and the global death rate is much higher, the Australian government’s decision to strictly follow medical advice and “go early and go hard” with lockdown measures was incredibly reassuring as I recovered.

In my case, I always felt that because I was in the hands of a competent, pandemic-prepared and well-resourced Australian healthcare system, I would eventually be fine. And so it proved.

My nine nights in the the hospital turned into another 10 days of home isolation before I was finally given the all clear to venture out into the new world of “exercise only” trips to local parks and near empty Sydney beaches.

THREE QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER:

- When did the SARS virus first hit Singapore and how many people ultimately died?

- When the coronavirus hit Australia how did the government characterise its response?

- What are the key reasons countries like Australia, Singapore and New Zealand have been successful in curbing the spread of the coronavirus?

Richard Hubbard is a finance and economics journalist with more than 35 years reporting from Australia, the UK, Asia and the United States. He is currently a freelance journalist based in Sydney. Hubbard covered the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s from Hong Kong and Singapore, and later the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis and its aftermath from London.

Richard Hubbard is a finance and economics journalist with more than 35 years reporting from Australia, the UK, Asia and the United States. He is currently a freelance journalist based in Sydney. Hubbard covered the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s from Hong Kong and Singapore, and later the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis and its aftermath from London.