Allegations of incest in a prominent family are forcing France to come to terms with sexual misconduct that until recently was widely overlooked.

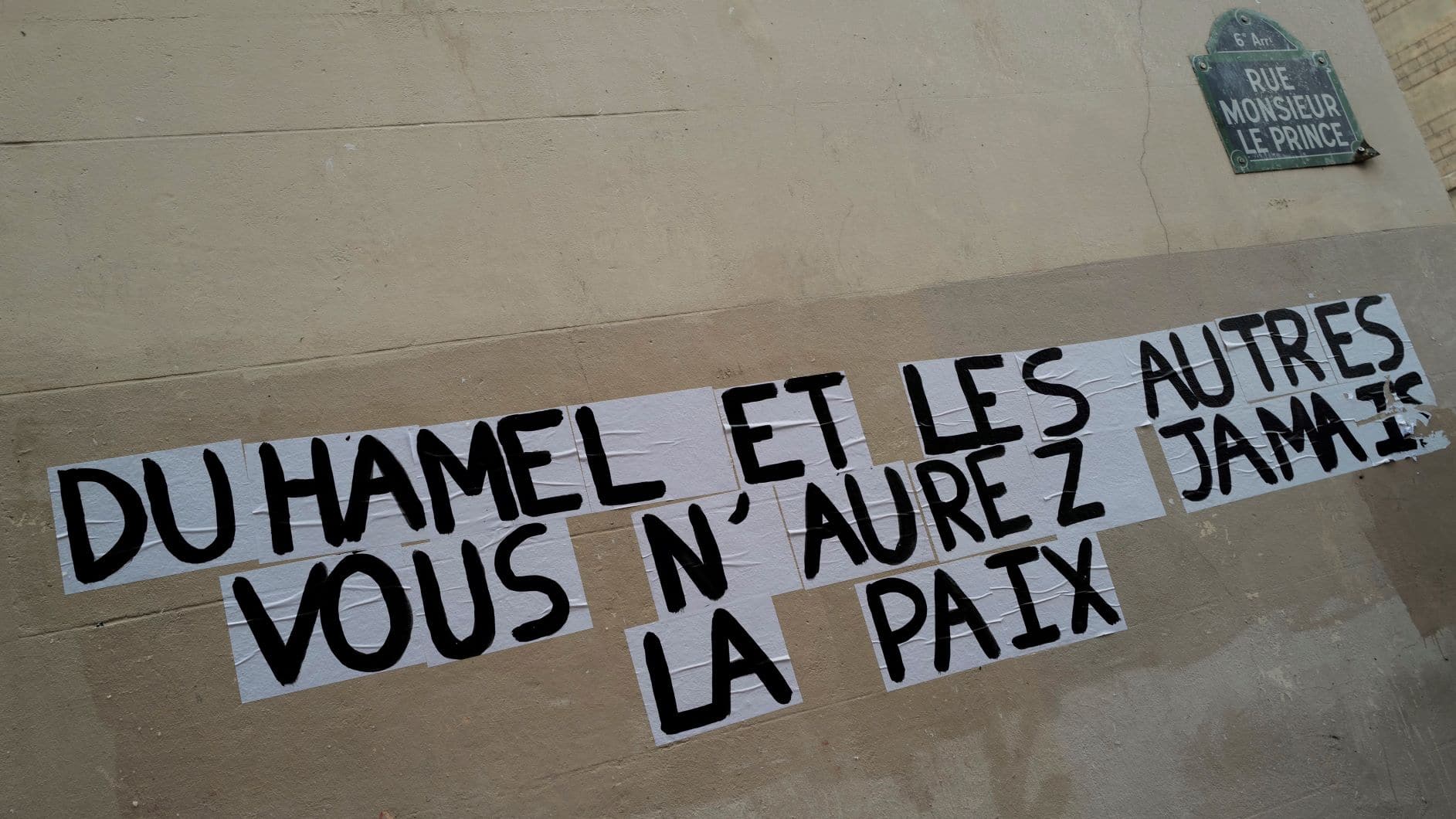

A sign on a wall reads “Duhamel, and the others, you will never be in peace,” referring to prominent French political expert Olivier Duhamel, in Paris, 19 January 2021. (AP Photo/Francois Mori)

Allegations of incest in one of France’s most eminent families have rocked the political elite and prompted parliament to debate tougher laws against the sexual abuse of children.

The case, which sparked social outrage comparable to #MeToo, raises broad questions about how prestigious institutions respond to scandal in their midst.

The cause célèbre is the latest example of a society struggling to come to terms with sexual conduct that in the recent past rarely made headlines but which in the age of social media, evolving moral standards and resolute victims is no longer tolerated.

Olivier Duhamel, a well-known constitutional lawyer, is accused by his step-daughter Camille Kouchner of repeatedly raping her twin brother when the children were in their early teens. Kouchner, now 45, made the charges in a book, “La Familia grande,” published in January.

Kouchner accused her mother, Evelyne Pisier, of protecting Duhamel, whom she married after divorcing the twins’ father, Bernard Kouchner, founder of the international charity Doctors Without Borders. Pisier, a law professor and political scientist, died in 2017.

One poll said 10% of French are victims of incest.

Existing French laws provide penalties ranging from five to 20 years in jail for sexual assault or rape of a person under the age of 15. In 2018, the cut-off date for prosecution was extended to 30 years after the victim’s 18th birthday rather than after the offence.

Some bills in the parliamentary pipeline would introduce a legal age of consent. That would make it impossible for an individual who is accused of having sex with someone under the specified age, which varies according to the bills, to claim that there was consent or that no violence, threat, coercion or surprise was involved.

Other proposals would remove the statute of limitations on sexual crimes against children altogether.

The National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE) estimates that every year in France, more than 200,000 people are victims of rape, attempted rape or sexual assault, and that most are minors.

It is notoriously difficult to obtain data, but some researchers believe that in nine out of 10 cases, the aggressor was a family member or a close friend of the victim.

The International Association of Victims of Incest (IAVI) says that 6.7 million people in France—10% of the population—declared themselves to be victims of incest. The figure is based on a survey of 1,033 people carried out for the IAVI by the French polling organization Ipsos.

Rape is grossly under-reported in most countries.

An IAVI report in December said previous estimates were too low and “after the #MeToo wave, we wanted to know the new figure.”

It is even harder to make statistical comparisons with other countries. The latest World Population Review, produced by an independent U.S.-based organization, says South Africa has the world’s highest incidence of rape, at 132 cases per 1,000 people. Sweden ranks sixth with 63.5 cases, while the United States has 27.3 and France 16.2.

But the report cautions that “rape is grossly under-reported” in most countries due to victim shaming, fear of reprisal, fear of family reactions and failure of the authorities to take complaints seriously.

What is more, legal definitions of rape vary widely from one country to another, while some jurisdictions permit forms of marriage that would be banned as incestuous elsewhere.

But INSEE says that in France, there are only 1,000 convictions for rape and 5,000 for sexual assault each year, while IAVI says the police dismiss 80% of complaints for lack of evidence.

‘Everyone knew.’

In a video released on social media on January 23, French President Emmanuel Macron said new steps would be taken in schools to identify victims of child abuse. “We are here, we are listening, we believe you, you will never again be alone,” he said.

In addition to regular medical tests in primary and secondary school, pupils would have two sessions with psychologists and free counselling would be provided for any child who had suffered abuse.

Teachers’ unions challenged the feasibility of the proposal, noting that only 600 positions for school doctors are currently filled and France has more than 12 million pupils.

Kouchner’s allegations quickly led to the resignations of several public figures.

Duhamel refused to comment but resigned as director of the governing body of the Paris Institute for Political Sciences. The elite institution, known as Sciences Po, is a training ground for senior officials. Its alumni include Macron, two former heads of state and several members of the current government.

On January 13, former justice minister Elisabeth Gigou resigned after five weeks as head of a commission investigating child abuse.

The same day, Marc Guillaume, formerly Macron’s top aide, quit the board of Sciences Po, saying “having known Olivier Duhamel for years, I feel betrayed and utterly condemn his actions.”

On February 9, Sciences Po Director Frédéric Mion yielded to a petition signed by 1,000 students and quit. Acknowledging “errors of judgement,” he admitted that he “heard rumors” about Duhamel in 2018, but he denied a published report that he had discussed them with Guillaume.

“The most shocking thing was that everyone knew but no one felt obliged to tell the police,” lawyer Dominique Attias, vice president of the European Bars Federation, told Le Monde newspaper. “Incest is not a family matter. It is a question of justice.”

#IncesteMeToo

In one sense, children in the best-off families may be most at risk. Sophie Legrand, a judge in the children’s court in the city of Tours, said social services authorities tend to intervene in families that are economically or socially deprived but “in very privileged social circles, there are rarely any signs of alert.”

But, as the Kouchner case shows, it takes something affecting a well-known family to attract media interest and bring to light events that were hidden by what Education Minister Michel Blanquer called “omerta,” the code of silence associated with the Mafia.

Kouchner’s book sparked a reaction on social media called #IncesteMeToo, echoing the #MeToo movement, launched in 2017 in the United States after accusations of rape and harassment against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, who was later sentenced to 23 years in jail.

The launch of #IncesteMeToo has encouraged large numbers of people to speak out. The French media have reported dozens of cases in recent weeks, with many victims referring to Kouchner’s book. Kouchner herself has said she felt free to write after the publication of a similar book, entitled “Consent,” last year.

The French version of #MeToo had a mixed reception. It was notably challenged by a group of 100 film actresses including Catherine Deneuve, but it later produced a fierce backlash against the awarding of the top prize at the 2019 Venice film festival to director Roman Polanski.

Polanski fled the United States in 1978, hours before he was due to be sentenced for sexually abusing a 13-year-old girl. He has denied any wrongdoing.

His award-winning film “An Officer and a Spy” retells the story of Alfred Dreyfus, a French 19th-Century army captain wrongfully jailed for espionage in an historic case of anti-Semitism. Polanski’s detractors accuse him of using the film to suggest that he, too, is a victim of injustice.

It is a suggestion that finds little sympathy in France today.

Three questions to consider:

- Why is rape so often an under-reported crime?

- Why might children in well-off families be more at risk of incest than others?

- What is a statute of limitations?

Robert Holloway had a long career at Agence France-Presse as a journalist and editor before becoming director of the AFP Foundation, the international media training arm of the global news agency. A British-born French citizen, he joined AFP in 1988 and served as Sydney bureau chief, foreign editor, head of the English desk in Paris, United Nations correspondent in New York, deputy managing editor and acting editor in chief.

Wow I did not know that South Africa had the most number of cases regarding rape in the world.