Many nations’ economies are bouncing back from COVID-19, putting upward pressure on prices. The jury’s out on whether inflation is back to haunt us.

Signs advertising jobs in Harmony, Pennsylvania, 21 May 2020. Increased economic growth in some economies is putting upward pressure on wages. (AP Photo/Keith Srakocic)

Countries across the industrialized world have in the past few months capitalized on rising vaccination rates to try, with varying degrees of success, to restore a bit of normalcy to their economies.

While this reopening has brought relief to pandemic-weary businesses and consumers, it has also revived a long-dormant menace: inflation.

Inflation, the speed at which the prices of goods and services increase, hit its fastest pace in a decade (or more) in the United States, the eurozone and Canada, among other nations.

In emerging markets, including Russia, Brazil, Poland and India, inflation is running well ahead of levels targeted by central banks.

After more than a decade of minuscule rises in both wages and living costs, the jump took many economists by surprise. Only last year, after all, most were fretting aloud that COVID-19 would doom the world to a deep and intractable economic downturn.

Booming demand as economies rebound from COVID

These concerns led governments all over the globe to pull out all the stops to keep businesses afloat and consumers spending. These ranged from the practical — direct payments to companies and individuals — to the rhetorical — for example, cheery admonitions during low infection periods to dine out with abandon.

Meanwhile, interest rates, which can track inflation expectations, remained at rock-bottom levels.

What few commentators expected was that economic growth would come roaring back this year and that surging demand would trigger a surge in the prices of long-lasting goods.

Jerome Powell, chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve central bank, called the pandemic recession in his country “the briefest yet deepest on record.”

“Booming demand for goods and the strength and speed of the reopening have led to shortages and bottlenecks, leaving the COVID-constrained supply side unable to keep up,” he told an economics conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, last month.

“The result has been elevated inflation in durable goods — a sector that has experienced an annual inflation rate well below zero over the past quarter century.”

Inflation, it seems, is back.

The price jump was dramatic enough to grab headlines, even in a hectic news period. In just the first few days of September:

The Guardian warned: “Inflation set to surge this autumn as Brexit and Covid combine.”

Bloomberg cautioned: “Stagflation Threatens to Upend the Global Economy.”

CNBC, meanwhile, cited the concerns of a respected economic historian: “Inflation could repeat the 1960s, when the Fed lost control, Niall Ferguson says.”

Inflation, it seems, is back. But for how long?

Are we heading, as Niall Ferguson suggests, for a period that echoes the 1960s?

Or, worse, the 1970s, which, along with dancing queens and loud jackets, was a prolonged period of “stagflation” — high prices coupled with stagnant job growth — followed by years of high interest rates as central banks sought to bring prices under control.

Or, as many in central banking circles believe, will price rises slow down once the world returns to normal?

Will price pressures fall back to pre-pandemic ranges?

The International Monetary Fund is banking on the latter. It said in July that price pressures were due “for the most part” to the effects of the pandemic and temporary supply bottlenecks and that inflation should fall back to “pre-pandemic ranges” in 2022. It added, however, that “uncertainty remains high.”

Many economists are not so sure.

Bank of Montreal Chief Economist Douglas Porter said that while he, along with most major forecasters, thinks price pressures would pass, he was in the “higher-for-longer” camp. After all, no major central bank was forecasting rates even close to current levels six months ago.

“We all knew there was going to be reopening pressure and we were still caught by surprise, so I have an issue when people dismiss this as nothing,” he said in an interview.

“I think it’s probably one of the bigger risks when we’re on the other side of the pandemic that we end up with a real inflation episode.”

The real key lies in consumer expectations. Inflation is something of a self-fulfilling prophecy. When we are convinced the car we have been eying will cost more next month, we are less likely to wait before rushing into the dealership. Inflation expectations breed rising demand. And rising demand pushes up prices.

And boom, an inflationary spiral is born.

Will labor shortages push up wages for good?

One of the signs Porter and other economists will be watching for is whether pandemic-related labor shortages lead to prolonged and widespread pay increases.

“A one-time level shift in wages, especially for people at the lower end of the income scale, that’s not a problem. That’s probably well-deserved,” Porter said.

“Where it will become an inflation issue if is if those wage increases start creeping their way up the income scale.”

This is not impossible. The Baby Boom generation is aging out of the workforce fast, and many younger high earners have taken advantage of the lockdown to take early retirement.

“There is still the real possibility that (the increase in inflation) turns into something ugly, and I think ultimately what it will depend on is whether we get a sustained increase in wages and a sustained change in psychology that really sticks and lasts,” Porter said.

Let’s suppose inflation does turn into a lasting trend. How will that affect a generation that has only ever known prices that, barring a small selection of suddenly trendy items, have stayed obediently in check?

Inflation can be good news for some wage earners and debtors.

First the good news. Unlike the 1970s, there appears to be upward pressure on wages this time around, particularly in entry-level jobs. Employer desperation to find staff is adding up to negotiating power for early-career workers.

Some of this may prove temporary. The ranks of job-seekers may swell once governments reduce pandemic support payments and health worries ease.

Still, there are longer-term trends, such as the rise in retirees, that argue otherwise.

According to the U.S. Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey released mid-August, for instance, a record 10.1 million jobs are available in that country right now.

In the United Kingdom, a combination of COVID-19 and the withdrawal from the European Union has caused massive shortages in agriculture, health care and transportation. This helped drive an 8.8% jump in wages in June. Now many economists are warning that a sharper-than-expected slowdown in July will prove short-lived.

If faster inflation does persist, it would also help those with student loans, mortgages and other debt, as long as central banks do not raise rates sharply to stem price rises. If interest rates stay tame, borrower debt levels will fall in real, inflation-adjusted terms every year.

Rising housing prices could mean inflation will stay.

But there are some distinct downsides.

First and foremost, there are property prices, which were soaring even before the pandemic. In many cities, they reached levels that froze hopeful young buyers out of the market. A rung on the property ladder would become an even more distant dream in an inflationary environment, when higher rents and living costs eat up down-payment funds.

That housing prices — and now rents — continue to surge in many economies, particularly North America, is a strong signal for Porter that inflation will stick around for a while.

“If you look back over history, after you get a boom in home prices, it tends to slowly but surely work its way into the CPI (consumer price index) over time, and right now we’re getting a boom in home prices,” he said.

“To me, it’s the housing element that might be almost the guarantee that we’re going to be left with somewhat higher inflation for a while.”

Other asset markets could in for a rough ride. Prolonged inflation would almost certainly spell an end to the long rise in stock prices and would inflict heavy damage on bonds.

And if the pace of inflation picks up enough to spook now sanguine major central bankers into big interest rate rises, stock investors and property buyers won’t be alone in hoping pop supergroup Abba is the only 1970s relic set for a revival.

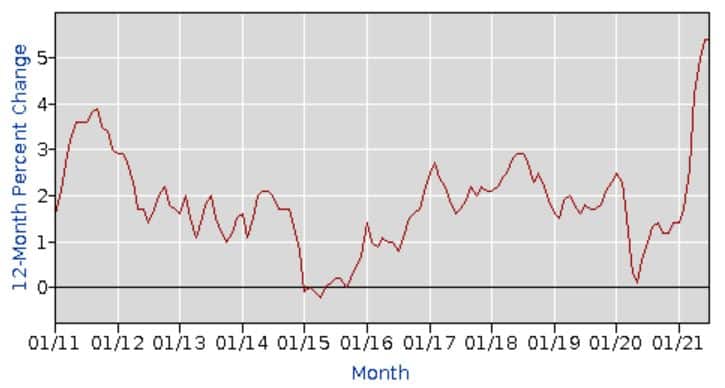

U.S. Consumer Price Inflation

U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) for All Urban Consumers (12-month percent change). The CPI is a measure of the average change over time in the prices paid by urban consumers for a market basket of consumer goods and services. It’s a widely watched inflation indicator. The index rose 5.4% for the 12 months in July. For more on this index and other U.S. economic indicators, you can look at data compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

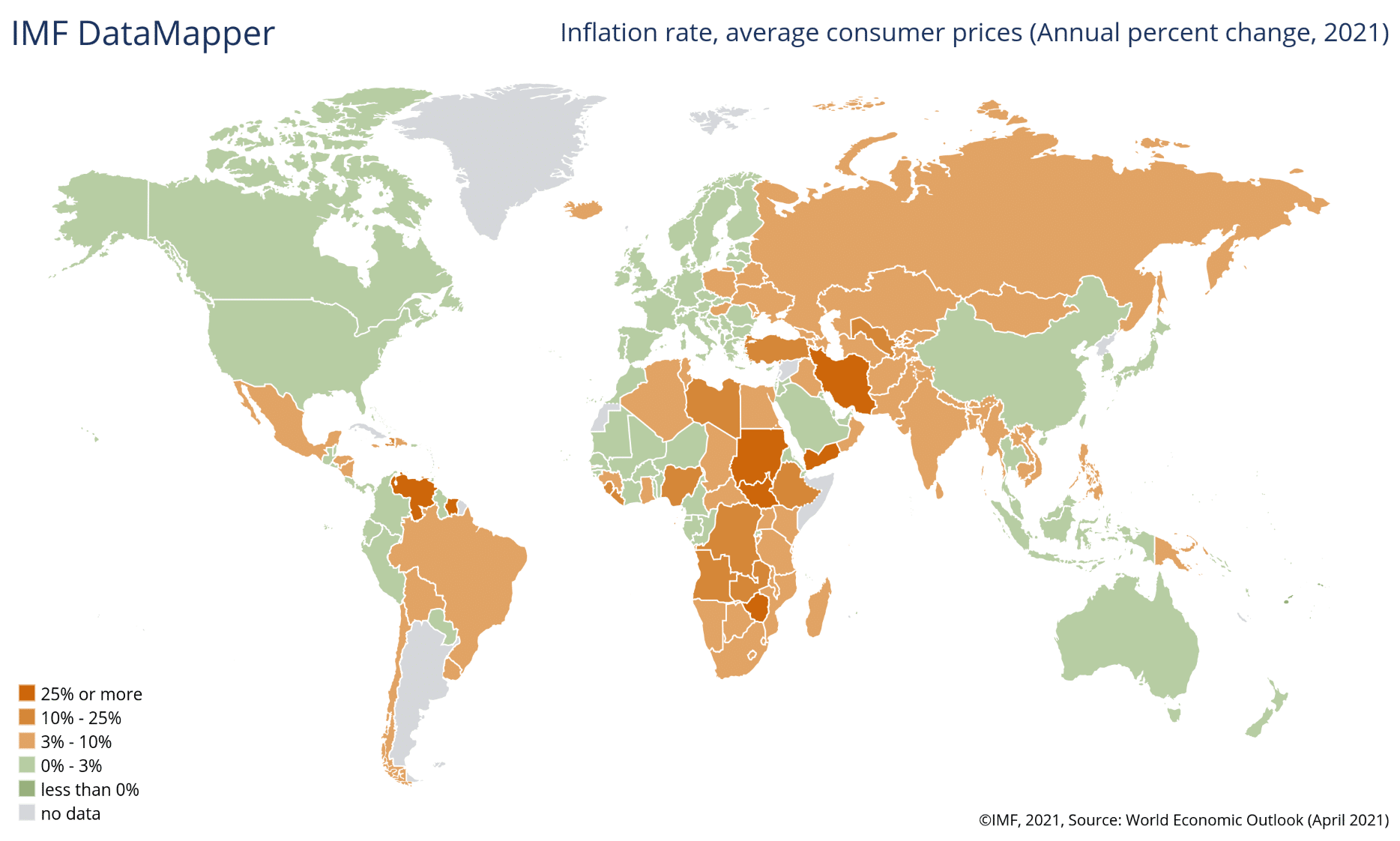

Earlier this year, the International Monetary Fund released its forecasts for inflation around the world in 2021, by country. The projected inflation rate, as measured by the annual percent change in consumer prices, for the world was 3.5% — 4.9% in emerging market and developing economies, 1.6% in advanced economies. The highest projected annual inflation rate was for Venezuela, at 5,500%

Questions to consider:

- What factors can lead to a prolonged increase in inflation in an economy?

- Why do many central bankers think the current surge in prices in wealthy nations might prove temporary?

- In what ways would a moderate pick-up in inflation be helpful to young people starting adult lives? In what ways unhelpful?

Sarah Edmonds is a former Reuters journalist who has worked in seven countries on three continents, variously as a financial markets and economics correspondent, news editor, bureau chief and news operations manager.

A cogent and well-written summary of our current dilemma. We will see what the next six months bring with the resurgence of COVID and the full impact of BREXIT in the U.K. Here in Canada, I will await the results of our upcoming federal election to make a judgment on our immediate prospects