Editors around the world explain how they’re helping kids to understand and cope with the news as Russia invades Ukraine.

From News-O-Matic, by a reader named Derin

A week before Russia invaded Ukraine, editor Joyce Grant at Canada’s Teaching Kids News conducted a Twitter poll of her teacher constituency to find out if students were talking about Ukraine.

“The answer was a resounding ‘No!,’” she said.

Once the shooting started, however, the children’s outlook changed, and editors needed to explore options about how to best to put the events in context.

Grant is not alone as editors of journalism for children address this latest variation of scary news.

“We certainly are getting reactions from kids,” said Russ Kahn, editor in chief at the U.S.-based News-O-Matic, after the invasion began.

News-O-Matic builds interactivity into its daily coverage. Hundreds of children write questions directly to him each month on all kinds of topics, such as this one from Rosie about Ukraine: “Dear Russ, I feel so bad for Ukraine! What did they ever do to Russia! I hope Russia gets punished for what they unjustly did.”

“Of course,” he said, “it was Emmemu who asked the billion-dollar question: ‘Why are Russians attacking?’”

News for kids about war is not some sanitized version of reality.

Kahn’s team is offering a variety of stories to give children a deeper understanding of “the ripple effects of Putin’s actions,” he said, referring to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

By February 22, News-O-Matic had already published a general story about the impending invasion. A story on February 24 focused on the global economic impact of the crisis, including news that the cost of crude oil had reached $100 a barrel for the first time since 2014.

Brazil’s Joca is taking a similar hybrid approach. “Talking to children to get their questions is something that we’re planning to do in next few days,” said Editor-in-Chief Maria Carolina Cristianini. “For now, because of the urgency of the issue, we’re are working on explaining to readers why a war is happening.”

Brazil’s Joca is taking a similar hybrid approach. “Talking to children to get their questions is something that we’re planning to do in next few days,” said Editor-in-Chief Maria Carolina Cristianini. “For now, because of the urgency of the issue, we’re are working on explaining to readers why a war is happening.”

France’s Playbac Press is relying on the approach that for more than two decades has served as the core strategy for getting it right when doing news for children: Ask them what they want to know. On February 27, they will have a virtual editorial meeting with the “kids editors for a day,” who will decide the focus of stories that professional journalists will then write.

“Our news is not some form of softened, sanitized version of reality,” Editor François Dufour said. “No subject is taboo, but it has to have an angle that is of interest to kids.”

Canada’s public broadcaster, CBC, is responding to questions by explaining the reality.

The first time CBC touched the story for its young audience was on February 24, with an explainer on why Russia invaded Ukraine. Senior Producer Lisa Fender said the goal was to break down the very complex history for kids aged nine-13.

“We have taken this approach because kids have told us that they want to know why the two countries are fighting,” Fender said.

In Singapore, it’s about a large country, Russia, invading a smaller country.

To make a war thousands of miles away relevant for children in Singapore, Serene Luo, schools editor at the Straits Times, believes it is important to tell her audience that it’s a story of a large country invading a smaller one. “The message is that if big countries can lord it over small countries, or ‘big eats small,’ then 700-square kilometer Singapore also is in a very precarious situation,” she said.

Finland has a special interest in the invasion. Finland borders Russia, was its “dutchy” from 1808 to 1917 and after World War Two ended up transferring 11% of its territory to the Soviet Union.

Fanny Fröman, head of Lasten uutiset (children’s news) at Helsingin Sanomat, began early in January to help Finnish children understand by making it easy for them to ask questions. “We did a video with background information and contact info to hotlines that children could call in case they felt scared,” Fröman said.

On February 24, a new story explained the situation and added a form for children to ask questions. “We have also posted about it on our Instagram account, to reach out to more children and give everyone the opportunity to ask questions,” Fröman said.

The plan is to continue on February 25 with an article and a YouTube video answering questions, with the print product of Lasten uutiset offering more coverage on March 2.

But Fröman decided to ease up on coverage for the weekly news broadcast to schools, also on February 25.

“Instead we just have a brief mention about what is going on,” she said. “Those who are more interested are referred to our website, which we will update more often.”

She continued: “This is also a way to keep the newscast a bit more positive. Many young kids will watch it in schools on Fridays, so we don’t want it to be too scary.”

‘Our aim is to provide hope rather than fear.’

These editors face a quandary because they rely on solutions-journalism techniques and prefer to focus on helpers in the stories they produce for children. In this case it’s been difficult to find helpers beyond the diplomats and world leaders who have so far failed to stem the fighting.

However, Germany’s DPA opted for a solutions focus in describing the hope that sanctions might work, and in its February 25 coverage, Austria’s Kleine Kinderzeitung spotlighted protesters, who could be construed as helping.

“We are answering children’s questions,” said staff member Weronika Peneshko. “Our aim is also to provide hope rather than fear, if possible.”

News-O-Matic editor Kahn answered Rosie with that kind of hope: “Thank you for sharing your feelings about the crisis in Ukraine,” he wrote. “We will have to see what world leaders do next.”

When it is too scary, some news operations offer children help for coping. News-O-Matic advises its youthful readers what to do, based on input from its on-staff psychologist and other experts. CBC created a video in 2019 explaining “how to deal with stories that leave people feeling worried or upset,” and at the end of its first story on the invasion of Ukraine published a number that any readers upset over the news could call for support.

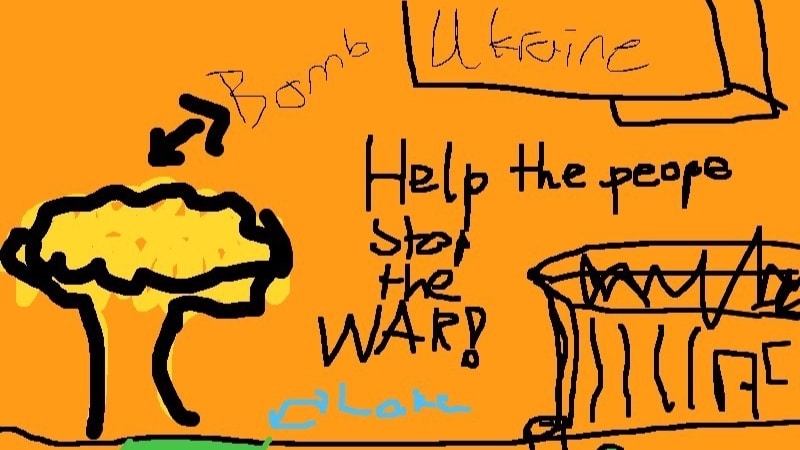

News-O-Matic can generate content for publication when it urges young readers to draw a picture to “help you let go of upset feelings.” News topics inspire readers to send in hundreds of drawings each month via an app. As of the evening of February 24, the newsroom team had not yet received any drawings about Ukraine, but it expects them soon.

“It may be hard to give concrete evidence from my perspective as a journalist as to the efficacy of art therapy,” Khan said, adding that News-O-Matic collects users’ drawings without any identifiable information such as age, location, last name, so the artwork tends to live in a vacuum.

“However, as a parent of a 12-year-old girl who has used art therapy to learn to handle intense emotions, I can attest first-hand to the power of art as a tool to cope and to heal,” Khan said.

(For updates on how news organizations around the world are covering events in Ukraine with youth in mind, please go to Global Youth & News Media’s special page.)

Three fun exercises:

- Take a look at some of the news stories mentioned in the article and think of at least three ways they differ from stories for adults about the conflict in Ukraine.

- In a group, select an article from a news source that targets adults and redo it for a 10-year-old. Think about what you needed to change and why.

- Create a political cartoon or illustration that you think would best illustrate this story and explain your reasoning and process.

Aralynn Abare McMane, an adviser to News Decoder, specializes in how news media can better serve the young. She directs the French nonprofit Global Youth & News Media and is the author of "The New News for Kids," an international report originally commissioned by the American Press Institute (2017) that she hopes to update and expand later this year. She encourages donations to Ukraine's Voices of Children Foundation.