When I arrived in Hong Kong half a century ago, it was just starting its explosive growth. Now it’s caught again in the middle of a big-power dispute.

Before Hong Kong’s old airport closed in 1998, it had just one runway, and airliners used to skim low over rooftops in hair-raising landings, 3 March 1998. (AP Photo/Vincent Yu)

Hong Kong is no stranger to being caught in the middle of big power rivalries.

Acquired by force by Britain from China in 1841, Hong Kong was invaded and brutally occupied by Japan in World War Two. When I first arrived in the city on the south China coast 50 years ago as a Reuters correspondent, it was recovering from bloody riots inspired by Communist China against British colonial rule.

But Hong Kong is nothing if not resilient.By the time China resumed control of Hong Kong in 1997, the city had made the most of its Western-type institutions and capitalist freedoms to not only survive, but thrive. The Economist magazine called it “slick and rich”.

Recently, the Financial Times said Hong Kong had played a central role in the two great stories of our era – the rise of China and the globalisation of the world economy.

But now the city of 7.4 million people is playing a sideshow role in the increasingly rancorous dispute between the United States and China. Among other measures, the United States has sanctioned Hong Kong officials for their alleged role in enforcing new security laws enacted by Beijing for the city.

Hong Kong has always been in the middle.

When I first came here in 1970, the city was calm, but it had a split personality that was in plain view.

In the heart of the main business district, now a forest of skyscrapers, was an immaculate, grass-covered sports ground, reserved for that quintessentially British game, cricket. One of my first assignments was to report on a match played on that ground. Among the teams there was just one local Hong Kong player.

But also in plain view at that time was China’s presence and influence in Hong Kong. Looming behind the cricket pitch was the local headquarters of Beijing’s Bank of China. It was adorned with an enormous banner trumpeting the ideology of Chinese leader Mao Zedong.

The cricket pitch has long since vanished, replaced by more of the gleaming and exorbitantly expensive real estate for which Hong Kong has become a byword.

In 1970, much of the top-quality infrastructure, for which Hong Kong is also renowned, had yet to appear.

The airport had just one runway. It protruded into the harbour that separates Hong Kong Island from the Kowloon part of the city. In a hair-raising landing approach, airliners skimmed low over rooftops, many festooned with laundry.

Newcomers feel Hong Kong’s energy.

Almost the only way to cross Hong Kong’s harbour was by the gently-chugging Star Ferry. The first of the city’s three cross-harbour tunnels did not open until 1972.

Also a prominent feature of the cityscape at that time were the many areas swathed with squatter settlements, homes for the flood of humanity that fled China after the Communists gained power in 1949.

All residents, not just the squatters, had to deal with rampaging corruption. The fast-growing population and the resulting stress on public amenities provided an ideal ground for the unscrupulous. Bribes called “tea money” had to be offered for all manner of services. Even ambulance crews demanded “tea money” to pick up the sick.

The problem was severe among the police, with a particularly notorious case involving a high-ranking expatriate. The graft plague was not properly dealt with until the establishment of a respected anti-corruption agency in 1974.

Hong Kong was flourishing economically and exuding the energy that I, like most newcomers, felt almost instantly on arrival. But it was still in the starting blocks of its mercurial development. Its main industries included toys, electronic goods, wigs and plastic flowers.

Many thousands of school age youngsters helped their families’ finances by finding abundant factory work. Among them was schoolgirl Betty Fu Heung-leung, who made a pittance during holidays working an 11-hour shift in a toy factory. Because she was below the legal age for workers, she borrowed an ID card from a girl who was old enough. That girl was aged 14.

Betty Fu is now my wife.

Hong Kong can cause confusion.

The mixing of East and West cultures in Hong Kong inevitably produces sometimes quirky confusion. An example of such a muddle involves a street sign, Alexander Terrace. Because the Chinese tradition is to write from right to left, the sign appeared with transposed spelling: Rednaxela Terrace. It’s still there today.

Hong Kong manages to arouse strong reactions, even among those who have never been here. Prince Albert, husband of Britain’s Queen Victoria, thought the place was funny. “Albert is so amused at my having got the island of Hong Kong,” the Queen wrote in 1841.

Whether Hong Kong itself, a flashpoint amidst rising superpower tensions, will have much for amusement in the near term remains to be seen.

Three questions to consider:

- How has Hong Kong changed since the author first arrived there in 1970?

- Why is the future of Hong Kong important to the world?

- How has your home town or city changed since your parents were youngsters?

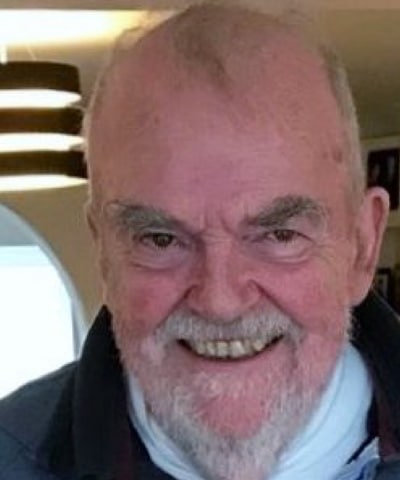

Jonathan Sharp joined Reuters after studying Chinese at university. That degree served him well, leading to two spells in Beijing. A 30-year career also took him to North America, the Middle East and South Africa, covering everything from wars to high-tech to the Olympics. His favorite posting was to Hong Kong, where he currently lives.