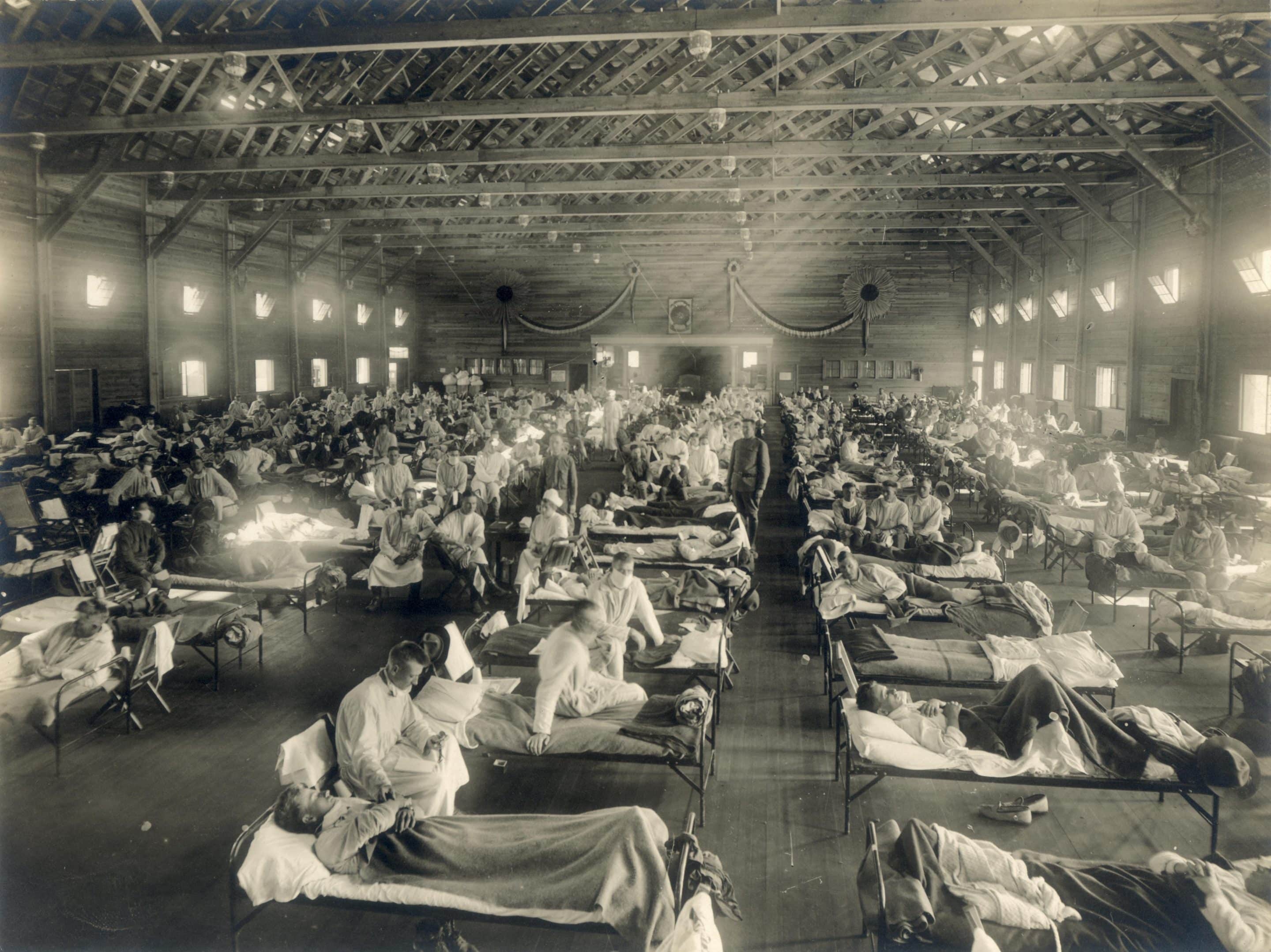

Both the 1918 flu pandemic and COVID-19 struck during crucial U.S. elections, infecting the nation’s leaders. But in 1918, a world war was raging.

A hospital in Kansas during the 1918 flu epidemic (Wikimedia Commons)

After six months of sheltering in place due to COVID-19, in late summer a friend and I finally ventured forth on an outing beyond the New York City area. Driving upstate, we took a dip in the lake at Fahnestock Memorial State Park.

When I told an old high school classmate about this park that bears his name, he said relatives established it to honor an uncle who had died in the 1918 influenza epidemic. Maj. Clarence Fahnestock, a U.S. army staff surgeon stationed in France during World War One, was infected by his patients and succumbed on October 5, 1918. He was 45.

For months in 2020, to applaud the bravery of healthcare and other essential workers, we New Yorkers went to our windows or gathered near hospitals daily at 7 p.m. But it’s hard to top the tribute of donating 2,400 acres (971 hectares) for a park to commemorate a doctor’s ultimate sacrifice.

Fahnestock Memorial Park (Photo by Susan Ruel)

So many threads connect the COVID-19 and 1918 flu pandemics. At the same Manhattan hospital where my neighbors and I salute the staff, nurses in 1918 administered “roof treatment” to their youngest influenza patients. Buffeted by fresh breezes from the nearby Hudson River, most of those children recovered, historian Albert Marrin writes in Very, Very, Very Dreadful: The Influenza Epidemic of 1918.

Marrin’s book — its title taken from Daniel Defoe’s Journal of a Plague Year, 1722 — describes conditions much less salutary in a children’s ward downtown at New York’s Bellevue Hospital. There, young flu patients slept three to a bed. In that era, the author explains, a major medical challenge was the “critical gap in physicians’ knowledge: they knew nothing about viruses.”

Then as now, New York officials scrambled to battle the pandemic, shutting down Broadway theaters, public libraries and private clubs. The public wore masks, and billboards declared it “unlawful to cough or sneeze.” But saloons, churches, department stores, streetcars and subways stayed open. “No Beer, No Work” was a popular outcry.

Even at the height of the 1918 pandemic, when on October 23 the New York City Health Department reported a record-breaking 851 deaths, the city’s public schools continued serving their one million pupils. Teachers monitored the kids, stopped them from congregating outside schools and sent home students who fell sick.

World War One and the 1918 flu pandemic were inextricably entwined.

In contrast to COVID-19 (known to take its heaviest toll among people over 65 and those with co-morbidities like obesity or diabetes), the 1918 flu pandemic hit adults aged 20-40, infants and toddlers especially hard, but was somewhat less deadly among school-age children aged 5 to 15.

Maj. Clarence Fahnestock (Photo courtesy of Columbia University)

Perhaps the most crucial difference between these two scourges is that just over a century ago, Dr. Fahnestock and millions of his comrades in arms were fighting World War One amid a plague so virulent that noted Johns Hopkins University epidemiologist Dr. Donald Burke has called it the “great-granddaddy of them all.”

It is now believed that in a year and a half, the influenza pandemic infected a third of the global population and killed at least 50 million people worldwide, including roughly 675,000 in the United States.

World War One and the 1918 epidemic were inextricably entwined. Given close quarters in military barracks, troop ships and trench warfare in Europe, the highly contagious strain of influenza spread like flames among soldiers on both sides, killing millions more than died in battle.

According to Marrin’s book, German troops, undernourished and less resistant due to blockades and food shortages, succumbed in greater numbers to what was then often called the “Spanish flu.” Neutral during the war, Spain was one of a few European nations to publish uncensored news about the flu epidemic, and thus ended up being unjustly named for and blamed for its outbreaks.

In the wake of the November 11, 1918 armistice, mass celebrations brought on yet another wave of contagion and death, as described in the novel Pale Horse, Pale Rider by noted U.S. author Katherine Anne Porter. She based it on her experiences barely surviving the pandemic as a young newspaperwoman in Colorado:

“… Something out of the Middle Ages. Did you ever see so many funerals, ever?… Pain all over, and you are in such danger as I can’t bear to think about.… All the theaters and nearly all the shops and restaurants are closed, and the streets have been full of funerals all day and ambulances all night….”

Wilson contracted influenza, Trump COVID-19.

Then-U.S. president Woodrow Wilson was criticized — as Donald Trump is today — for mishandling a pandemic. In public pronouncements, Wilson apparently never mentioned influenza, preferring to focus instead on winning the war. But — as has Trump — Wilson eventually fell victim to the epidemic of his era. He contracted influenza in Paris in 1919 while negotiating the Treaty of Versailles.

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson (Wikimedia Commons)

Some historians believe this illness weakened Wilson’s negotiating stamina. He ended up caving on several of his key proposals for the treaty, designed to alleviate post-war bitterness. Lingering resentments over the terms of this treaty are often cited among the causes of World War Two.

In another interesting historical footnote, future U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt, then assistant secretary of the Navy, became critically ill with influenza while sailing home from France in 1918 and barely survived.

With the contentious 2020 U.S. presidential election voting already underway, it’s worth recalling the nation’s sharply contested 1918 midterm election.

In the month leading up to that November 5 election day, some 195,000 people died of influenza. The week of October 23 — with 21,000 lives lost — was the nation’s deadliest since the Civil War. State and local officials called for social distancing, mask wearing and to varying degrees the closure of bars, churches, theaters and schools. Campaigning candidates were forced to rely more on media interviews or direct mail advertising.

Strong partisans divisions arose at times, with some claiming: “Vote Republican, and you need have no fear of the flu.” In New York, Republicans were accused of hobbling the gubernatorial campaign of Democratic candidate Al Smith by cancelling his speeches and limiting crowds. Despite the alleged hindrances, Smith went on to win.

Voter turnout in the 1918 U.S. midterm was a full 10% lower than four years earlier — a phenomenon widely blamed on quarantines and fears of infection. In the end, Wilson’s Democratic Party lost its majority in both houses of Congress for the first time since 1908.

Trump-Biden is shaping up as a referendum on the U.S. response to COVID-19.

Since COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic in March 2020, more than 80 elections have taken place worldwide — from France and Poland to South Korea and Sri Lanka. South Korea’s was a notable success, with voting staggered over three days and clear public communications; voter turnout (66%) was the highest in 28 years. By contrast, Poland’s election, done partially by mail, ended with allegations that many absentee ballots went uncounted.

In the United States — with 4% of the global population but about 20% of worldwide COVID-19 deaths — voters in many states are already casting their ballots early or by mail. The pandemic has greatly hampered campaigning and get-out-the-vote efforts by Democrats. Citing safety concerns, they have held back from holding big events or doing grassroots voter canvassing.

The Trump campaign, on the other hand, kept holding packed campaign rallies until the president was diagnosed on October 1 with COVID-19. The Republican Party continues its voter outreach and last month claimed to be knocking on the doors of a million households a week.

These days, the number of COVID-19 cases in the United States has soared above 7 million, with more than 210,000 dead, many millions unemployed and the nation’s economy in tatters. Amid fears of even greater losses if as expected the seasonal flu season coincides with the pandemic, the Trump-Biden contest is shaping up as a referendum on the national response to this public health disaster.

As with the 1918 flu epidemic, history will be the judge.

Three questions to consider:

- What are some of the chief similarities between the COVID-19 and the 1918 influenza pandemics?

- What are some major differences between these two pandemics?

- Taking a history lesson from the 1918 flu epidemic, list some suggestions for more effective responses to managing the COVID-19 pandemic — and preparing for future threats of this kind.

Susan Ruel worked on the international desks of the Associated Press and United Press International and reported for UPI from Shanghai, San Francisco and Washington. She has written and edited articles and books for the United Nations, including reports from Nigeria. A former journalism professor with a PhD in writing and literature, she co-authored two French books on U.S. media history and was a Fulbright scholar in West Africa. Since 2005, she has been writing and editing for healthcare non-profits in New York.

Great article!!

Very well done, Susie — well-researched and informative!